Synopsis: “The Man Who Came Early” is a short story by Poul Anderson, first published in June 1956 in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. An elderly Icelandic farmer from the tenth century recounts to a Christian priest the mysterious arrival of a stranger who, after a great storm, appeared wandering along the shore. Dressed in unfamiliar clothing and carrying strange artifacts, the newcomer claimed to come from a thousand years in the future and from a great nation that did not yet exist. Though skeptical—and at times taking him for a madman—a family decides to take him in and offer him shelter. Grateful, the man tries to adapt to that primitive society while recounting astonishing tales of his own time.

The Man Who Came Early

Poul Anderson

(Full story)

YES, WHEN A MAN grows old he has heard so much that is strange there’s little more can surprise him. They say the king in Miklagard has a beast of gold before his high seat which stands up and roars. I have it from Eilif Eiriksson, who served in the guard down yonder, and he is a steady fellow when not drunk. He has also seen the Greek fire used, it burns on water.

So, priest, I am not unwilling to believe what you say about the White Christ. I have been in England and France myself, and seen how the folk prosper. He must be a very powerful god, to ward so many realms . . . and did you say that everyone who is baptized will be given a white robe? I would like to have one. They mildew, of course, in this cursed wet Iceland weather, but a small sacrifice to the house-elves should—No sacrifices? Come now! I’ll give up horseflesh if I must, my teeth not being what they were, but every sensible man knows how much trouble the elves make if they’re not fed.

Well, let’s have another cup and talk about it. How do you like the beer? It’s my own brew, you know. The cups I got in England, many years back. I was a young man then . . . time goes, time goes. Afterward I came back and inherited this, my father’s farm, and have not left it since. Well enough to go in viking as a youth, but grown older you see where the real wealth lies: here, in the land and the cattle.

Stoke up the fires, Hjalti. It’s getting cold. Sometimes I think the winters are colder than when I was a boy. Thorbrand of the Salmondale says so, but he believes the gods are angry because so many are turning from them. You’ll have trouble winning Thorbrand over, priest. A stubborn man. Myself, I am open-minded, and willing to listen at least.

Now, then. There is one point on which I must set you right. The end of the world is not coming in two years. This I know.

And if you ask me how I know, that’s a very long tale, and in some ways a terrible one. Glad I am to be old, and safe in the earth before that great tomorrow comes. It will be an eldritch time before the frost giants fare loose . . . oh, very well, before the angel blows his battle horn. One reason I hearken to your preaching is that I know the White Christ will conquer Thor. I know Iceland is going to be Christian erelong, and it seems best to range myself on the winning side.

No, I’ve had no visions. This is a happening of five years ago, which my own household and neighbors can swear to. They mostly did not believe what the stranger told; I do, more or less, if only because I don’t think a liar could wreak so much harm. I loved my daughter, priest, and after the trouble was over I made a good marriage for her. She did not naysay it, but now she sits out on the ness-farm with her husband and never a word to me; and I hear he is ill pleased with her silence and moodiness, and spends his nights with an Irish leman. For this I cannot blame him, but it grieves me.

Well, I’ve drunk enough to tell the whole truth now, and whether you believe it or not makes no odds to me. Here . . . you, girls! . . . fill these cups again, for I’ll have a dry throat before I finish the telling.

———

It begins, then, on a day in early summer, five years ago. At that time, my wife Ragnhild and I had only two unwed children still living with us: our youngest son Helgi, of seventeen winters, and our daughter Thorgunna, of eighteen. The girl, being fair, had already had suitors. But she refused them, and I am not one who would compel his daughter. As for Helgi, he was ever a lively one, good with his hands but a breakneck youth. He is now serving in the guard of King Olaf of Norway. Besides these, of course, we had about ten housefolk—two thralls, two girls to help with the women’s work, and half a dozen hired carles. This is not a small stead.

You have seen how my land lies. About two miles to the west is the bay; the thorps at Reykjavik are some five miles south. The land rises toward the Long Jökull, so that my acres are hilly; but it’s good hay land, and we often find driftwood on the beach. I’ve built a shed down there for it, as well as a boathouse.

We had had a storm the night before—a wild huge storm with lightning flashes across heaven, such as you seldom get in Iceland—so Helgi and I were going down to look for drift. You, coming from Norway, do not know how precious wood is to us here, who have only a few scrubby trees and must get our timber from abroad. Back there men have often been burned in their houses by their foes, but we count that the worst of deeds, though it’s not unheard of.

As I was on good terms with my neighbors, we took only hand weapons. I bore my ax, Helgi a sword, and the two carles we had with us bore spears. It was a day washed clean by the night’s fury, and the sun fell bright on long, wet grass. I saw my stead lying rich around its courtyard, sleek cows and sheep, smoke rising from the roofhole of the hall, and knew I’d not done so ill in my lifetime. My son Helgi’s hair fluttered in the low west wind as we left the buildings behind a ridge and neared the water. Strange how well I remember all which happened that day; somehow it was a sharper day than most.

When we came down to the strand, the sea was beating heavy, white and gray out to the world’s edge, smelling of salt and kelp. A few gulls mewed above us, frightened off a cod washed onto the shore. I saw a litter of no few sticks, even a baulk of timber . . . from some ship carrying it that broke up during the night, I suppose. That was a useful find, though as a careful man I would later sacrifice to be sure the owner’s ghost wouldn’t plague me.

We had fallen to and were dragging the baulk toward the shed when Helgi cried out. I ran for my ax as I looked the way he pointed. We had no feuds then, but there are always outlaws.

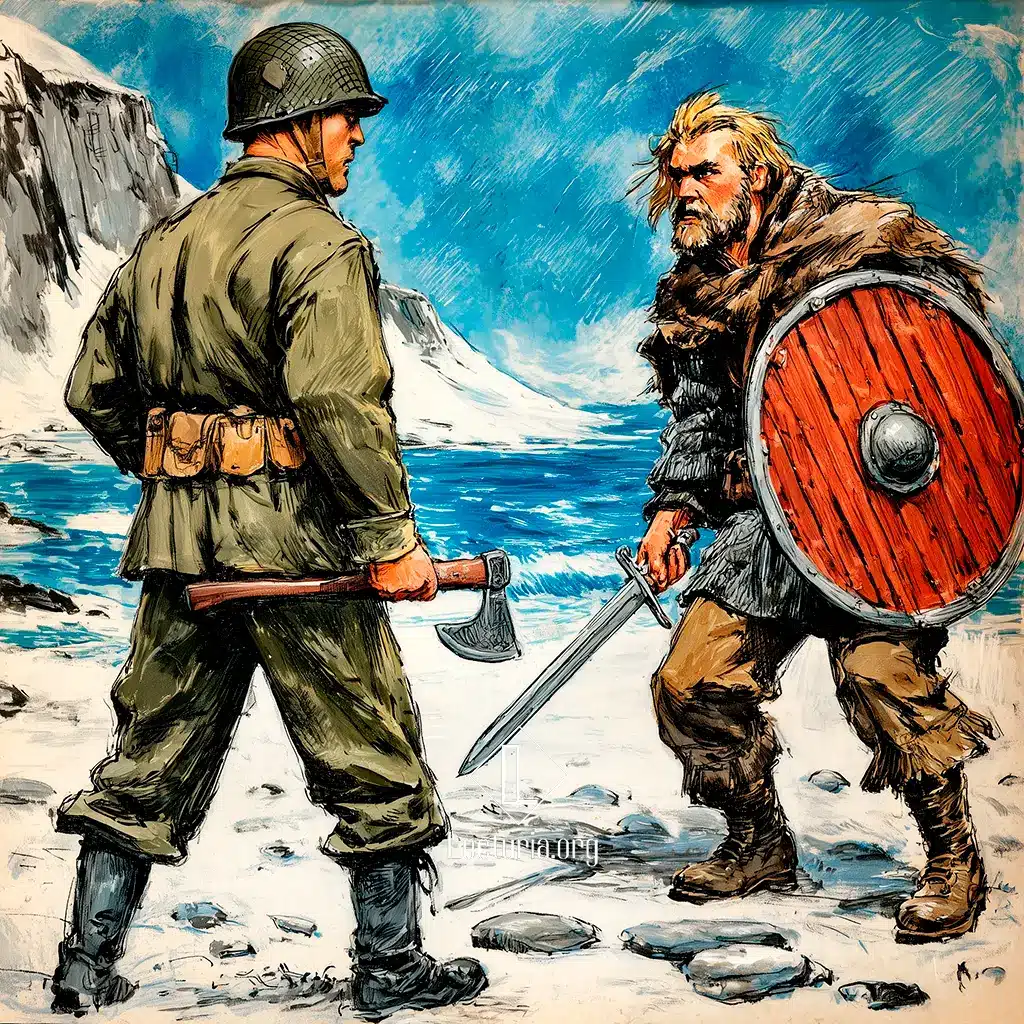

This newcomer seemed harmless, though. Indeed, as he stumbled nearer across the black sand I thought him quite unarmed and wondered what had happened. He was a big man and strangely clad—he wore coat and breeches and shoes like anyone else, but they were of odd cut, and he bound his trousers with leggings rather than straps. Nor had I ever seen a helmet like his: it was almost square, and came down toward his neck, but it had no nose guard. And this you may not believe, but it was not metal, yet had been cast in one piece!

He broke into a staggering run as he drew close, flapped his arms and croaked something. The tongue was none I had heard, and I have heard many; it was like dogs barking. I saw that he was clean-shaven and his black hair cropped short, and thought he might be French. Otherwise he was a young man, and good-looking, with blue eyes and regular features. From his skin I judged that he spent much time indoors. However, he had a fine manly build.

“Could he have been shipwrecked?” asked Helgi.

“His clothes are dry and unstained,” I said; “nor has he been wandering long, for no stubble is on his chin. Yet I’ve heard of no strangers guesting hereabouts.”

We lowered our weapons, and he came up to us and stood gasping. I saw that his coat and the shirt underneath were fastened with bonelike buttons rather than laces, and were of heavy weave. About his neck he had fastened a strip of cloth tucked into his coat. These garments were all in brownish hues. His shoes were of a sort new to me, very well stitched. Here and there on his coat were bits of brass, and he had three broken stripes on each sleeve; also a black band with white letters, the same letters on his helmet. Those were not runes, but Roman—thus: MP. He wore a broad belt, with a small clublike thing of metal in a sheath at the hip and also a real club.

“I think he must be a warlock,” muttered my carle Sigurd. “Why else so many tokens?”

“They may only be ornament, or to ward against witchcraft,” I soothed him. Then, to the stranger: “I hight Ospak Ulfsson of Hillstead. What is your errand?”

He stood with his chest heaving and a wildness in his eyes. He must have run a long way. At last he moaned and sat down and covered his face.

“If he’s sick, best we get him to the house,” said Helgi. I heard eagerness; we see few faces here.

“No . . . no . . .” The stranger looked up. “Let me rest a moment—”

He spoke the Norse tongue readily enough, though with a thick accent not easy to follow and with many foreign words I did not understand.

The other carle, Grim, hefted his spear. “Have vikings landed?” he asked.

“When did vikings ever come to Iceland?” I snorted. “It’s the other way around.”

The newcomer shook his head as if it had been struck. He got shakily to his feet. “What happened?” he said. “What became of the town?”

“What town?” I asked reasonably.

“Reykjavik!” he cried. “Where is it?”

“Five miles south, the way you came—unless you mean the bay itself,” I said.

“No! There was only a beach, and a few wretched huts, and—”

“Best not let Hialmar Broadnose hear you call his thorp that,” I counseled.

“But there was a town!” he gasped. “I was crossing the street in a storm, and heard a crash, and then I stood on the beach and the town was gone!”

“He’s mad,” said Sigurd, backing away. “Be careful. If he starts to foam at the mouth, it means he’s going berserk.”

“Who are you?” babbled the stranger. “What are you doing in those clothes? Why the spears?”

“Somehow,” said Helgi, “he does not sound crazed, only frightened and bewildered. Something evil has beset him.”

“I’m not staying near a man under a curse!” yelped Sigurd, and started to run away.

“Come back!” I bawled. “Stand where you are or I’ll cleave your louse-bitten head.”

That stopped him, for he had no kin who would avenge him; but he would not come closer. Meanwhile the stranger had calmed down to the point where he could talk somewhat evenly.

“Was it the aitsjbom?” he asked. “Has the war started?”

He used that word often, aitsjbom, so I know it now, though I am unsure of what it means. It seems to be a kind of Greek fire. As for the war, I knew not which war he meant, and told him so.

“We had a great thunderstorm last night,” I added. “And you say you were out in one too. Maybe Thor’s hammer knocked you from your place to here.”

“But where is here?” he answered. His voice was more dulled than otherwise, now that the first terror had lifted.

“I told you. This is Hillstead, which is on Iceland.”

“But that’s where I was!” he said. “Reykjavik . . . what happened? Did the aitsjbom destroy everything while I lay witless?”

“Nothing has been destroyed,” I said.

“Does he mean the fire at Olafsvik last month?” wondered Helgi.

“No, no, no!” Again he buried his face in his hands. After a while he looked up and said: “See here. I am Sardjant Gerald Robbins of the United States army base on Iceland. I was in Reykjavik and got struck by lightning or something. Suddenly I was standing on the beach, and lost my head and ran. That’s all. Now, can you tell me how to get back to the base?”

Those were more or less his words, priest. Of course, we did not grasp half of them, and made him repeat several times and explain. Even then we did not understand, save that he was from some country called the United States of America, which he said lies beyond Greenland to the west, and that he and some others were on Iceland to help our folk against their foes. This I did not consider a lie—more a mistake or imagining. Grim would have cut him down for thinking us stupid enough to swallow that tale, but I could see that he meant it.

Talking cooled him further. “Look here,” he said, in too calm a tone for a feverish man, “maybe we can get at the truth from your side. Has there been no war you know of? Nothing which—Well, look here. My country’s men first came to Iceland to guard it against the Germans. Now it is the Russians, but then it was the Germans. When was that?”

Helgi shook his head. “That never happened that I know of,” he said. “Who are these Russians?” We found out later that the Gardariki folk were meant. “Unless,” Helgi said, “the old warlocks—”

“He means the Irish monks,” I explained. “A few dwelt here when the Norsemen came, but they were driven out. That was, hm, somewhat over a hundred years ago. Did your kingdom once help the monks?”

“I never heard of them!” he said. The breath sobbed in his throat. “You . . . didn’t you Icelanders come from Norway?”

“Yes, about a hundred years ago,” I answered patiently. “After King Harald Fairhair laid the Norse lands under him and—”

“A hundred years ago!” he whispered. I saw whiteness creep up beneath his skin. “What year is this?”

We gaped at him. “Well, it’s the second year after the great salmon catch,” I tried.

“What year after Christ, I mean,” he prayed hoarsely.

“Oh, so you are a Christian? Hm, let me think . . . I talked with a bishop in England once, we were holding him for ransom, and he said . . . let me see . . . I think he said this Christ man lived a thousand years ago, or maybe a little less.”

“A thousand—” Something went out of him. He stood with glassy eyes—yes, I have seen glass, I told you I am a traveled man—he stood thus, and when we led him toward the garth he went like a small child.

———

You can see for yourself, priest, that my wife Ragnhild is still good to look upon even in eld, and Thorgunna took after her. She was—is—tall and slim, with a dragon’s hoard of golden hair. She being a maiden then, the locks flowed loose over her shoulders. She had great blue eyes and a heart-shaped face and very red lips. Withal she was a merry one, and kindhearted, so that she was widely loved. Sverri Snorrason went in viking when she refused him, and was slain, but no one had the wit to see that she was unlucky.

We led this Gerald Samsson—when I asked, he said his father was named Sam—we led him home, leaving Sigurd and Grim to finish gathering the driftwood. Some folks would not have a Christian in their house, for fear of witchcraft, but I am a broad-minded man, and Helgi, at his age, was wild for anything new. Our guest stumbled over the fields as if blind, but seemed to rouse when we entered the yard. His gaze went around the buildings that enclose it, from the stables and sheds to the smokehouse, the brewery, the kitchen, the bathhouse, the god shrine, and thence to the hall. And Thorgunna was standing in the doorway.

Their gazes locked for a little, and I saw her color but thought nothing of it then. Our shoes rang on the flagging as we crossed the yard and kicked the dogs aside. My two thralls halted in cleaning the stables to gawp, until I got them back to work with the remark that a man good for naught else was always a pleasing sacrifice. That’s one useful practice you Christians lack; I’ve never made a human offering myself, but you know not how helpful is the fact that I could do so.

We entered the hall, and I told the folk Gerald’s name and how we had found him. Ragnhild set her maids hopping, to stoke up the fire in the middle trench and fetch beer, while I led Gerald to the high seat and sat down by him. Thorgunna brought us the filled horns. His standing was not like yours, for whom we use our outland cups.

Gerald tasted the brew and made a face. I felt somewhat offended, for my beer is reckoned good, and asked him if aught was wrong. He laughed with a harsh note and said no, but he was used to beer that foamed and was not sour.

“And where might they make such?” I wondered testily.

“Everywhere,” he said. “Iceland, too—no. . . .” He stared before him in an empty wise. “Let’s say . . . in Vinland.”

“Where is Vinland?” I asked.

“The country to the west whence I came. I thought you knew. . . . Wait a bit.” He frowned. “Maybe I can find out something. Have you heard of Leif Eiriksson?”

“No,” I said. Since then it has struck me that this was one proof of his tale, for Leif Eiriksson is now a well-known chief; and I also take more seriously those yarns of land seen by Bjarni Herjulfsson.

“His father, Erik the Red?” went on Gerald.

“Oh yes,” I said. “If you mean the Norseman who came hither because of a manslaughter, and left Iceland in turn for the same reason, and has now settled with his friends in Greenland.”

“Then this is . . . a little before Leif’s voyage,” he muttered. “The late tenth century.”

“See here,” broke in Helgi, “we’ve been forbearing with you, but now is no time for riddles. We save those for feasts and drinking bouts. Can you not say plainly whence you come and how you got here?”

Gerald looked down at the floor, shaking.

“Let the man alone, Helgi,” said Thorgunna. “Can you not see he’s troubled?”

He raised his head and gave her the look of a hurt dog that someone has patted. The hall was dim; enough light seeped in the loft windows that no candles were lit, but not enough to see well by. Nevertheless, I marked a reddening in both their faces.

Gerald drew a long breath and fumbled about. His clothes were made with pockets. He brought out a small parchment box and from it took a little white stick that he put in his mouth. Then he took out another box, and a wooden stick there from which burst into flame when he scratched. With the fire he kindled the stick in his mouth, and sucked in the smoke.

We stared. “Is that a Christian rite?” asked Helgi.

“No . . . not just so.” A wry, disappointed smile twisted his lips. “I thought you’d be more surprised, even terrified.”

“It’s something new,” I admitted, “but we’re a sober folk on Iceland. Those fire sticks could be useful. Did you come to trade in them?”

“Hardly.” He sighed. The smoke he breathed in seemed to steady him, which was odd, because the smoke in the hall had made him cough and water at the eyes. “The truth is, well, something you will not believe. I can hardly believe it myself.”

We waited. Thorgunna stood leaning forward, her lips parted.

“That lightning bolt—” Gerald nodded wearily. “I was out in the storm, and somehow the lightning must have smitten me in just the right way, a way that happens only once in many thousands of times. It threw me back into the past.”

Those were his words, priest. I did not understand, and told him so.

“It’s hard to grasp,” he agreed. “God give that I’m merely dreaming. But if this is a dream I must endure till I awaken. . . . Well, look. I was born one thousand, nine hundred, and thirty-three years after Christ, in a land to the west which you have not yet found. In the twenty-fourth year of my life, I was in Iceland with my country’s war host. The lightning struck me, and now, now it is less than one thousand years after Christ, and yet I am here—almost a thousand years before I was born, I am here!”

We sat very still. I signed myself with the Hammer and took a long pull from my horn. One of the maids whimpered, and Ragnhild whispered so fiercely I could hear: “Be still. The poor fellow’s out of his head. There’s no harm in him.”

I thought she was right, unless maybe in the last part. The gods can speak through a madman, and the gods are not always to be trusted. Or he could turn berserker, or he could be under a heavy curse that would also touch us.

He slumped, gazing before him. I caught a few fleas and cracked them while I pondered. Gerald noticed and asked with some horror if we had many fleas here.

“Why, of course,” said Thorgunna. “Have you none?”

“No.” He smiled crookedly. “Not yet.”

“Ah,” she sighed, “then you must be sick.”

She was a level-headed girl. I saw her thought, and so did Ragnhild and Helgi. Clearly, a man so sick that he had no fleas could be expected to rave. We might still fret about whether we could catch the illness, but I deemed this unlikely; his woe was in the head, maybe from a blow he had taken. In any case, the matter was come down to earth now, something we could deal with.

I being a godi, a chief who holds sacrifices, it behooved me not to turn a stranger out. Moreover, if he could fetch in many of those fire-kindling sticks, a profitable trade might be built up. So I said Gerald should go to rest. He protested, but we manhandled him into the shut-bed, and there he lay tired and was soon asleep. Thorgunna said she would take care of him.

———

The next eventide I meant to sacrifice a horse, both because of the timber we had found and to take away any curse that might be on Gerald. Furthermore, the beast I picked was old and useless, and we were short of fresh meat. Gerald had spent the morning lounging moodily around the garth, but when I came in at noon to eat I found him and my daughter laughing.

“You seem to be on the road to health,” I said.

“Oh yes. It . . . could be worse for me.” He sat down at my side as the carles set up the trestle table and the maids brought in the food. “I was ever much taken with the age of the vikings, and I have some skills.”

“Well,” I said, “if you have no home, we can keep you here for a while.”

“I can work,” he said eagerly. “I’ll be worth my pay.”

Now I knew he was from afar, because what chief would work on any land but his own, and for hire at that? Yet he had the easy manner of the high-born, and had clearly eaten well throughout his life. I overlooked that he had made me no gifts; after all, he was shipwrecked.

“Maybe you can get passage back to your United States,” said Helgi. “We could hire a ship. I’m fain to see that realm.”

“No,” said Gerald bleakly. “There is no such place. Not yet.”

“So you still hold to that idea you came from tomorrow?” grunted Sigurd. “Crazy notion. Pass the pork.”

“I do,” said Gerald. Calm had come upon him. “And I can prove it.”

“I don’t see how you speak our tongue, if you hail from so far away,” I said. I would not call a man a liar to his face, unless we were swapping friendly brags, but—

“They speak otherwise in my land and time,” he said, “but it happens that in Iceland the tongue changed little since the old days, and because my work had me often talking with the folk, I learned it when I came here.”

“If you are a Christian,” I said, “you must bear with us while we sacrifice tonight.”

“I’ve naught against that,” he said. “I fear I never was a very good Christian. I’d like to watch. How is it done?”

I told him how I would smite the horse with a hammer before the god, and cut its throat, and sprinkle the blood about with willow twigs; thereafter we would butcher the carcass and feast. He said hastily:

“Here’s my chance to prove what I am. I have a weapon that will kill the horse with, with a flash of lightning.”

“What is it?” I wondered. We crowded around while he took the metal club out of its sheath and showed it to us. I had my doubts; it looked well enough for hitting a man, I reckoned, but had no edge, though a wondrously skillful smith had forged it. “Well, we can try,” I said. You have seen how on Iceland we are less concerned to follow the rites exactly than they are in the older countries.

Gerald showed us what else he had in his pockets. There were some coins of remarkable roundness and sharpness, though neither gold nor true silver; a tiny key; a stick with lead in it for writing; a flat purse holding many bits of marked paper. When he told us gravely that some of this paper was money, Thorgunna herself had to laugh. Best was a knife whose blade folded into the handle. When he saw me admiring that, he gave it to me, which was well done for a shipwrecked man. I said I would give him clothes and a good ax, as well as lodging for as long as needful.

No, I don’t have the knife now. You shall hear why. It’s a pity, for that was a good knife, though rather small.

“What were you ere the war arrow went out in your land?” asked Helgi. “A merchant?”

“No,” said Gerald. “I was an . . . endjinur . . . that is, I was learning how to be one. A man who builds things, bridges and roads and tools . . . more than just an artisan. So I think my knowledge could be of great value here.” I saw a fever in his eyes. “Yes, give me time and I’ll be a king.”

“We have no king on Iceland,” I grunted. “Our forefathers came hither to get away from kings. Now we meet at the Things to try suits and pass new laws, but each man must get his own redress as best he can.”

“But suppose the one in the wrong won’t yield?” he asked.

“Then there can be a fine feud,” said Helgi, and went on to relate some of the killings in past years. Gerald looked unhappy and fingered his gun. That is what he called his fire-spitting club. He tried to rally himself with a joke about now, at last, being free to call it a gun instead of something else. That disquieted me, smacked of witchcraft, so to change the talk I told Helgi to stop his chattering of manslaughter as if it were sport. With law shall the land be built.

“Your clothing is rich,” said Thorgunna softly. “Your folk must own broad acres at home.”

“No,” he said, “our . . . our king gives each man in the host clothes like these. As for my family, we owned no farm, we rented our home in a building where many other families also dwelt.”

I am not purse-proud, but it seemed to me he had not been honest, a landless man sharing my high seat like a chief. Thorgunna covered my huffiness by saying, “You will gain a farm later.”

After sunset we went out to the shrine. The carles had built a fire before it, and as I opened the door the wooden Odin appeared to leap forth. My house has long invoked him above the others. Gerald muttered to my daughter that it was a clumsy bit of carving, and since my father had made it I was still more angry with him. Some folks have no understanding of the fine arts.

Nevertheless, I let him help me lead the horse forth to the altar stone. I took the blood bowl in my hands and said he could now slay the beast if he would. He drew his gun, put the end behind the horse’s ear, and squeezed. We heard a crack, and the beast jerked and dropped with a hole blown through its skull, wasting the brains. A clumsy weapon. I caught a whiff, sharp and bitter like that around a volcano. We all jumped, one of the women screamed, and Gerald looked happy. I gathered my wits and finished the rest of the sacrifice as was right. Gerald did not like having blood sprinkled over him, but then he was a Christian. Nor would he take more than a little of the soup and flesh.

Afterward Helgi questioned him about the gun, and he said it could kill a man at bowshot distance but had no witchcraft in it, only use of some tricks we did not know. Having heard of the Greek fire, I believed him. A gun could be useful in a fight, as indeed I was to learn, but it did not seem very practical—iron costing what it does, and months of forging needed for each one.

I fretted more about the man himself.

And the next morning I found him telling Thorgunna a great deal of foolishness about his home—buildings as tall as mountains, and wagons that flew, or went without horses. He said there were eight or nine thousand thousands of folk in his town, a burgh called New Jorvik or the like. I enjoy a good brag as well as the next man, but this was too much, and I told him gruffly to come along and help me get in some strayed cattle.

———

After a day scrambling around the hills I saw that Gerald could hardly tell a cow’s bow from her stern. We almost had the strays once, but he ran stupidly across their path and turned them, so the whole work was to do again. I asked him with strained courtesy if he could milk, shear, wield scythe or flail, and he said no, he had never lived on a farm.

“That’s a shame,” I remarked, “for everyone on Iceland does, unless he be outlawed.”

He flushed at my tone. “I can do enough else,” he answered. “Give me some tools and I’ll show you good metalwork.”

That brightened me, for truth to tell, none of our household was a gifted smith. “That’s an honorable trade,” I said, “and you can be of great help. I have a broken sword and several bent spearheads to be mended, and it were no bad idea to shoe the horses.” His admission that he did not know how to put on a shoe was not very dampening to me then.

We had returned home as we talked, and Thorgunna came angrily forward. “That’s no way to treat a guest, Father,” she said. “Making him work like a carle, indeed!”

Gerald smiled. “I’ll be glad to work,” he said. “I need a . . . a stake . . . something to start me afresh. Also, I want to repay a little of your kindness.”

Those words made me mild toward him, and I said it was not his fault they had different ways in the United States. On the morrow he could begin in the smithy, and I would pay him, yet he would be treated as an equal since craftsmen are valued. This earned him black looks from the housefolk.

That evening he entertained us well with stories of his home; true or not, they made good listening. However, he had no real polish, being unable to compose a line of verse. They must be a raw and backward lot in the United States. He said his task in the war host had been to keep order among the troops. Helgi said this was unheard of, and he must be bold who durst offend so many men, but Gerald said folk obeyed him out of fear of the king. When he added that the term of a levy in the United States was two years, and that men could be called to war even in harvest time, I said he was well out of a country with so ruthless and powerful a lord.

“No,” he answered wistfully, “we are a free folk, who say what we please.”

“But it seems you may not do as you please,” said Helgi.

“Well,” Gerald said, “we may not murder a man just because he aggrieves us.”

“Not even if he has slain your own kin?” asked Helgi.

“No. It is for the . . . the king to take vengeance, on behalf of the whole folk whose peace has been broken.”

I chuckled. “Your yarns are cunningly wrought,” I said, “but there you’ve hit a snag. How could the king so much as keep count of the slaughters, let alone avenge them? Why, he’d not have time to beget an heir!”

Gerald could say no more for the laughter that followed.

———

The next day he went to the smithy, with a thrall to pump the bellows for him. I was gone that day and night, down to Reykjavik to dicker with Hjalmar Broadnose about some sheep. I invited him back for an overnight stay, and we rode into my steading with his son Ketill, a red-haired sulky youth of twenty winters who had been refused by Thorgunna.

I found Gerald sitting gloomily on a bench in the hall. He wore the clothes I had given him, his own having been spoilt by ash and sparks; what had he awaited, the fool? He talked in a low voice with my daughter.

“Well,” I said as I trod in, “how went the tasks?”

My man Grim snickered. “He ruined two spearheads, but we put out the fire he started ere the whole smithy burned.”

“How’s this?” I cried. “You said you were a smith.”

Gerald stood up, defiant. “I worked with different tools, and better ones, at home,” he replied. “You do it otherwise here.”

They told me he had built up the fire too hot; his hammer had struck everywhere but the place it should; he had wrecked the temper of the steel through not knowing when to quench it. Smithcraft takes years to learn, of course, but he might have owned to being not so much as an apprentice.

“Well,” I snapped, “what can you do, then, to earn your bread?” It irked me to be made a ninny of before Hjalmar and Ketill, whom I had told about the stranger.

“Odin alone knows,” said Grim. “I took him with me to ride after your goats, and never have I seen a worse horseman. I asked him if maybe he could spin or weave, and he said no.”

“That was no question to ask a man!” flared Thorgunna. “He should have slain you for it.”

“He should indeed,” laughed Grim. “But let me carry on the tale. I thought we would also repair your bridge over the foss. Well, he can barely handle a saw, but he nigh took his own foot off with the adze.”

“We don’t use those tools, I tell you!” Gerald doubled his fists and looked close to tears.

I motioned my guests to sit down. “I don’t suppose you can butcher or smoke a hog, either,” I said, “or salt a fish or turf a roof.”

“No.” I could hardly hear him.

“Well, then, man, whatever can you do?”

“I—” He could get no words out.

“You were a warrior,” said Thorgunna.

“Yes, that I was!” he said, his face kindling.

“Small use on Iceland when you have no other skills,” I grumbled, “but maybe, if you can get passage to the eastlands, some king will take you in his guard.” Myself I doubted it, for a guardsman needs manners that will do credit to his lord; but I had not the heart to say so.

Ketill Hjalmarsson had plainly not liked the way Thorgunna stood close to Gerald and spoke for him. Now he leered and said: “I might also doubt your skill in fighting.”

“That I have been trained for,” said Gerald grimly.

“Will you wrestle with me?” asked Ketill.

“Gladly!” spat Gerald.

Priest, what is a man to think? As I grow older, I find life to be less and less the good-and-evil, black-and-white thing you call it; we are each of us some hue of gray. This useless fellow, this spiritless lout who could be asked if he did women’s work and not lift ax, went out into the yard with Ketill Hjalmarsson and threw him three times running. He had a trick of grabbing the clothes as Ketill rushed him . . . I cried a stop when the youth was nearing murderous rage, praised them both, and filled the beer horns. But Ketill brooded sullen on the bench the whole evening.

Gerald said something about making a gun like his own, but bigger, a cannon he called it, which would sink ships and scatter hosts. He would need the help of smiths, and also various stuffs. Charcoal was easy, and sulfur could be found by the volcanoes, I suppose, but what is this saltpeter?

Too, being wary by now, I questioned him closely as to how he would make such a thing. Did he know just how to mix the powder? No, he admitted. What size must the gun be? When he told me—at least as long as a man—I laughed and asked him how a piece that size could be cast or bored, supposing we could scrape together so much iron. This he did not know either.

“You haven’t the tools to make the tools to make the tools,” he said. I don’t understand what he meant by that. “God help me, I can’t run through a thousand years of history by myself.”

He took out the last of his little smoke sticks and lit it. Helgi had tried a puff earlier and gotten sick, though he remained a friend of Gerald’s. Now my son proposed to take a boat in the morning and go with him and me to Ice Fjord, where I had some money outstanding I wanted to collect. Hjalmar and Ketill said they would come along for the trip, and Thorgunna pleaded so hard that I let her come too.

“An ill thing,” mumbled Sigurd. “The land trolls like not a woman aboard a vessel. It’s unlucky.”

“How did your fathers bring women to this island?” I grinned.

Now I wish I had listened to him. He was not a clever man, but he often knew whereof he spoke.

———

At this time I owned a half-share in a ship that went to Norway, bartering wadmal for timber. It was a profitable business until she ran afoul of vikings during the uproar while Olaf Tryggvason was overthrowing Jarl Haakon there. Some men will do anything to make a living—thieves, cutthroats, they ought to be hanged, the worthless robbers pouncing on honest merchantmen. Had they any courage or honor they would go to Ireland, which is full of plunder.

Well, anyhow, the ship was abroad, but we had three boats and took one of these. Grim went with us others: myself, Helgi, Hjalmar, Ketill, Gerald, and Thorgunna. I saw how the castaway winced at the cold water as we launched her, yet afterward took off his shoes and stockings to let his feet dry. He had been surprised to learn we had a bathhouse—did he think us savages?—but still, he was dainty as a girl and soon moved upwind of our feet.

We had a favoring breeze, so raised mast and sail. Gerald tried to help, but of course did not know one line from another and got them fouled. Grim snarled at him and Ketill laughed nastily. But erelong we were under weigh, and he came and sat by me where I had the steering oar.

He must have lain long awake thinking, for now he ventured shyly: “In my land they have . . . will have . . . a rig and rudder which are better than these. With them, you can sail so close to the wind that you can crisscross against it.”

“Ah, our wise sailor offers us redes,” sneered Ketill.

“Be still,” said Thorgunna sharply. “Let Gerald speak.”

Gerald gave her a look of humble thanks, and I was not unwilling to listen. “This is something which could easily be made,” he said. “While not a seaman, I’ve been on such boats myself and know them well. First, then, the sail should not be square and hung from a yardarm, but three-cornered, with the two bottom corners lashed to a yard swiveling fore and aft from the mast; and there should be one or two smaller headsails of the same shape. Next, your steering oar is in the wrong place. You should have a rudder in the stern, guided by a bar.” He grew eager and traced the plan with his fingernail on Thorgunna’s cloak. “With these two things, and a deep keel, going down about three feet for a boat this size, a ship can move across the wind . . . thus.”

Well, priest, I must say the idea has merits, and were it not for the fear of bad luck—for everything of his was unlucky—I might yet play with it. But the drawbacks were clear, and I pointed them out in a reasonable way.

“First and worst,” I said, “this rudder and deep keel would make it impossible to beach the ship or go up a shallow river. Maybe they have many harbors where you hail from, but here a craft must take what landings she can find, and must be speedily launched if there should be an attack.”

“The keel can be built to draw up into the hull,” he said, “with a box around so that water can’t follow.”

“How would you keep dry rot out of the box?” I answered. “No, your keel must be fixed, and must be heavy if the ship is not to capsize under so much sail as you have drawn. This means iron or lead, ruinously costly.

“Besides,” I said, “this mast of yours would be hard to unstep when the wind dropped and oars came out. Furthermore, the sails are the wrong shape to stretch as an awning when one must sleep at sea.”

“The ship could lie out, and you go to land in a small boat,” he said. “Also, you could build cabins aboard for shelter.”

“The cabins would get in the way of the oars,” I said, “unless the ship were hopelessly broad-beamed or else the oarsmen sat below a deck; and while I hear that galley slaves do this in the southlands, free men would never row in such foulness.”

“Must you have oars?” he asked like a very child.

Laughter barked along the hull. The gulls themselves, hovering to starboard where the shore rose dark, cried their scorn.

“Do they have tame winds in the place whence you came?” snorted Hjalmar. “What happens if you’re becalmed—for days, maybe, with provisions running out—”

“You could build a ship big enough to carry many weeks’ provisions,” said Gerald.

“If you had the wealth of a king, you might,” said Helgi. “And such a king’s ship, lying helpless on a flat sea, would be swarmed by every viking from here to Jomsborg. As for leaving her out on the water while you make camp, what would you have for shelter, or for defense if you should be trapped ashore?”

Gerald slumped. Thorgunna said to him gently: “Some folk have no heart to try anything new. I think it’s a grand idea.”

He smiled at her, a weary smile, and plucked up the will to say something about a means for finding north in cloudy weather; he said a kind of stone always pointed north when hung from a string. I told him mildly that I would be most interested if he could find me some of this stone; or if he knew where it was to be had, I could ask a trader to fetch me a piece. But this he did not know, and fell silent. Ketill opened his mouth, but got such an edged look from Thorgunna that he shut it again. His face declared what a liar he thought Gerald to be.

The wind turned crank after a while, so we lowered the mast and took to the oars. Gerald was strong and willing, though awkward; however, his hands were so soft that erelong they bled. I offered to let him rest, but he kept doggedly at the work.

Watching him sway back and forth, under the dreary creak of the holes, the shaft red and wet where he gripped it, I thought much about him. He had done everything wrong which a man could do—thus I imagined then, not knowing the future—and I did not like the way Thorgunna’s eyes strayed to him and rested. He was no man for my daughter, landless and penniless and helpless. Yet I could not keep from liking him. Whether his tale was true or only madness, I felt he was honest about it; and surely whatever way by which he came hither was a strange one. I noticed the cuts on his chin from my razor; he had said he was not used to our kind of shaving and would grow a beard. He had tried hard. I wondered how well I would have done, landing alone in this witch country of his dreams, with a gap of forever between me and my home.

Maybe that same wretchedness was what had turned Thorgunna’s heart. Women are a kittle breed, priest, and you who have forsworn them belike understand them as well as I who have slept with half a hundred in six different lands. I do not think they even understand themselves. Birth and life and death, those are the great mysteries, which none will ever fathom, and a woman is closer to them than a man.

The ill wind stiffened, the sea grew gray and choppy under low, leaden clouds, and our headway was poor. At sunset we could row no more, but must pull in to a small, unpeopled bay, and make camp as well as could be on the strand.

We had brought firewood and timber along. Gerald, though staggering with weariness, made himself useful, his sulfury sticks kindling the blaze more easily than flint and steel. Thorgunna set herself to cook our supper. We were not much warded by the boat from a lean, whining wind; her cloak fluttered like wings and her hair blew wild above the streaming flames. It was the time of light nights, the sky a dim, dusky blue, the sea a wrinkled metal sheet, and the land like something risen out of dream mists. We men huddled in our own cloaks, holding numbed hands to the fire and saying little.

I felt some cheer was needed, and ordered a cask of my best and strongest ale broached. An evil Norn made me do that, but no man escapes his weird. Our bellies seemed the more empty now when our noses drank in the sputter of a spitted joint, and the ale went swiftly to our heads. I remember declaiming the death-song of Ragnar Hairybreeks for no other reason than that I felt like declaiming it.

Thorgunna came to stand over Gerald where he sat. I saw how her fingers brushed his hair, ever so lightly, and Ketill Hjalmarsson did too. “Have they no verses in your land?” she asked.

“Not like yours,” he said, glancing up. Neither of them looked away again. “We sing rather than chant. I wish I had my gittar here—that’s a kind of harp.”

“Ah, an Irish bard,” said Hjalmar Broadnose.

I remember strangely well how Gerald smiled, and what he said in his own tongue, though I know not the meaning: “Only on me mither’s side, begorra.” I suppose it was magic.

“Well, sing for us,” laughed Thorgunna.

“Let me think,” he said. “I shall have to put it in Norse words for you.” After a little while, still staring at her through the windy gloaming, he began a song. It had a tune I liked, thus:

From this valley they tell me you’re leaving.

I will miss your bright eyes and sweet smile.

You will carry the sunshine with you

That has brightened my life all the while. . . .

I don’t remember the rest, save that it was not quite seemly.

When he had finished, Hjalmar and Grim went over to see if the meat was done. I spied a glimmer of tears in my daughter’s eyes. “That was a lovely thing,” she said.

Ketill sat straight. The flames splashed his face with wild, running red. A rawness was in his tone: “Yes, we’ve found what this fellow can do. Sit about and make pretty songs for the girls. Keep him for that, Ospak.”

Thorgunna whitened, and Helgi clapped hand to sword. Gerald’s face darkened and his voice grew thick: “That was no way to talk. Take it back.”

Ketill rose. “No,” he said. “I’ll ask no pardon of an idler living off honest yeomen.”

He was raging, but had kept sense enough to shift the insult from my family to Gerald alone. Otherwise he and his father would have had the four of us to deal with. As it was, Gerald stood too, fists knotted at his sides, and said: “Will you step away from here and settle this?”

“Gladly!” Ketill turned and walked a few yards down the beach, taking his shield from the boat. Gerald followed. Thorgunna stood stricken, then snatched his ax and ran after him.

“Are you going weaponless?” she shrieked.

Gerald stopped, looking dazed. “I don’t want anything like that,” he said. “Fists—”

Ketill puffed himself up and drew sword. “No doubt you’re used to fighting like thralls in your land,” he said. “So if you’ll crave my pardon, I’ll let this matter rest.”

Gerald stood with drooped shoulders. He stared at Thorgunna as if he were blind, as if asking her what to do. She handed him the ax.

“So you want me to kill him?” he whispered.

“Yes,” she answered.

Then I knew she loved him, for otherwise why should she have cared if he disgraced himself?

Helgi brought him his helmet. He put it on, took the ax, and went forward.

“Ill is this,” said Hjalmar to me. “Do you stand by the stranger, Ospak?”

“No,” I said. “He’s no kin or oath-brother of mine. This is not my quarrel.”

“That’s good,” said Hjalmar. “I’d not like to fight with you. You were ever a good neighbor.”

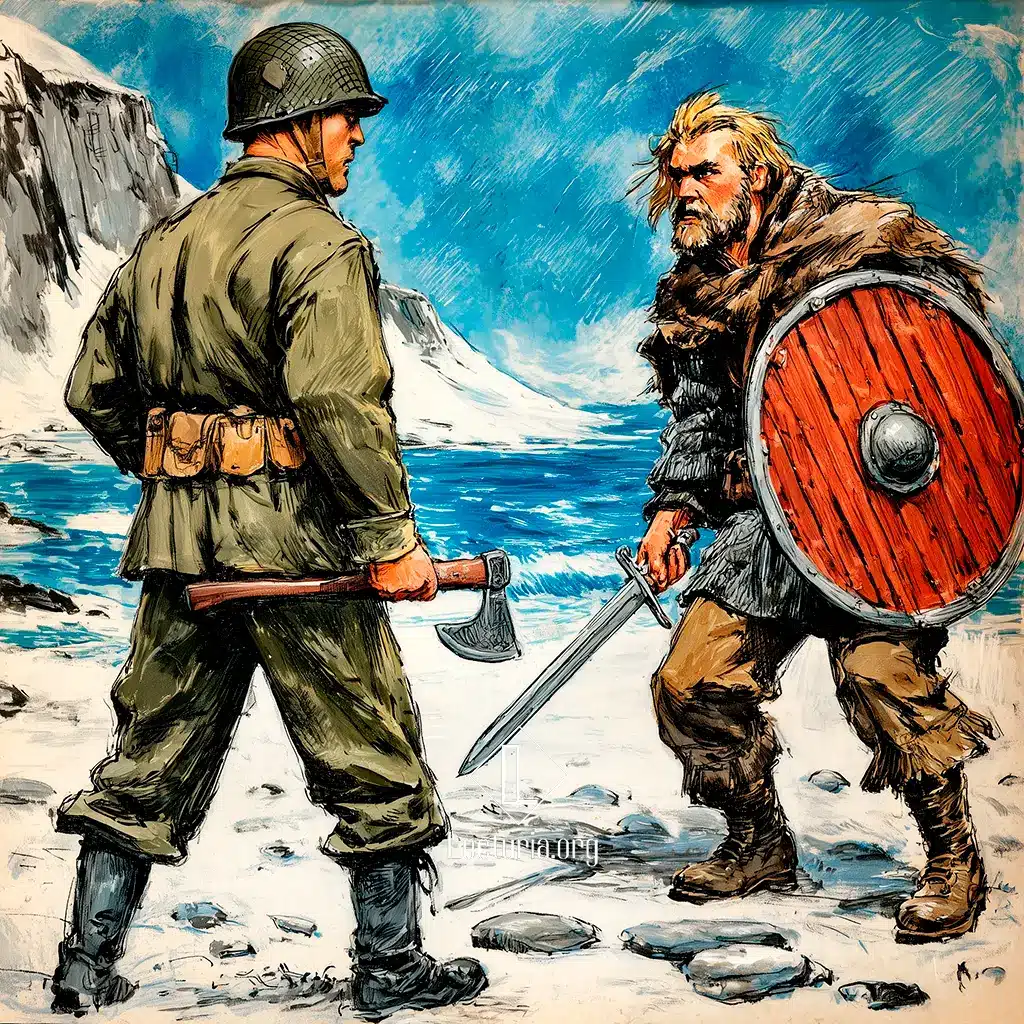

We stepped forth together and staked out the ground. Thorgunna told me to lend Gerald my sword, so he could use a shield too, but the man looked oddly at me and said he would rather have the ax. They squared off before each other, he and Ketill, and began fighting.

This was no holmgang, with rules and a fixed order of blows and first blood meaning victory. There was death between those two. Drunk though the lot of us were, we saw that and so had not tried to make peace. Ketill stormed in with the sword whistling in his hand. Gerald sprang back, wielding the ax awkwardly. It bounced off Ketill’s shield. The youth grinned and cut at Gerald’s legs. Blood welled forth to stain the ripped breeches.

What followed was butchery. Gerald had never used a battle-ax before. So it turned in his grasp and he struck with the flat of the head. He would have been hewn down at once had Ketill’s sword not been blunted on his helmet and had he not been quick on his feet. Even so, he was erelong lurching with a dozen wounds.

“Stop the fight!” Thorgunna cried, and sped toward them. Helgi caught her arms and forced her back, where she struggled and kicked till Grim must help. I saw grief on my son’s face, but a wolfish glee on the carle’s.

Ketill’s blade came down and slashed Gerald’s left hand. He dropped the ax. Ketill snarled and readied to finish him. Gerald drew his gun. It made a flash and a barking noise. Ketill fell. Blood gushed from him. His lower jaw was blown off and the back of his skull was gone.

A stillness came, where only the wind and the sea had voice.

Then Hjalmar trod forth, his mouth working but otherwise a cold steadiness over him. He knelt and closed his son’s eyes, as a token that the right of vengeance was his. Rising, he said: “That was an evil deed. For that you shall be outlawed.”

“It wasn’t witchcraft,” said Gerald in a stunned tone. “It was like a . . . a bow. I had no choice. I didn’t want to fight with more than my fists.”

I got between them and said the Thing must decide this matter, but that I hoped Hjalmar would take weregild for Ketill.

“But I killed him to save my own life!” protested Gerald.

“Nevertheless, weregild must be paid, if Ketill’s kin will take it,” I explained. “Because of the weapon, I think it will be doubled, but that is for the Thing to judge.”

Hjalmar had many other sons, and it was not as if Gerald belonged to a family at odds with his own, so I felt he would agree. However, he laughed coldly and asked where a man lacking wealth would find the silver.

Thorgunna stepped up with a wintry calm and said we would pay. I opened my mouth, but when I saw her eyes I nodded. “Yes, we will,” I said, “in order to keep the peace.”

“So you make this quarrel your own?” asked Hjalmar.

“No,” I answered. “This man is no blood of mine. But if I choose to make him a gift of money to use as he wishes, what of it?”

Hjalmar smiled. Sorrow stood in his gaze, but he looked on me with old comradeship.

“One day he may be your son-in-law,” he said. “I know the signs, Ospak. Then indeed he will be of your folk. Even helping him now in his need will range you on his side.”

“And so?” asked Helgi, most softly.

“And so, while I value your friendship, I have sons who will take the death of their brother ill. They’ll want revenge on Gerald Samsson, if only for the sake of their good names, and thus our two houses will be sundered and one manslaying will lead to another. It has happened often enough ere now.” Hjalmar sighed. “I myself wish peace with you, Ospak, but if you take this killer’s side it must be otherwise.”

I thought for a moment, thought of Helgi lying with his head cloven, of my other sons on their steads drawn to battle because of a man they had never seen, I thought of having to wear byrnies each time we went down for driftwood and never knowing when we went to bed if we would wake to find the house ringed in by spearmen.

“Yes,” I said, “You are right, Hjalmar. I withdraw my offer. Let this be a matter between you and him alone.”

We gripped hands on it.

Thorgunna uttered a small cry and flew into Gerald’s arms. He held her close. “What does this mean?” he asked slowly.

“I cannot keep you any longer,” I said, “but maybe some crofter will give you a roof. Hjalmar is a law-abiding man and will not harm you until the Thing has outlawed you. That will not be before they meet in fall. You can try to get passage out of Iceland ere then.”

“A useless one like me?” he replied in bitterness.

Thorgunna whirled free and blazed that I was a coward and a perjurer and all else evil. I let her have it out before I laid my hands on her shoulders.

“I do this for the house,” I said. “The house and the blood, which are holy. Men die and women weep, but while the kindred live our names are remembered. Can you ask a score of men to die for your hankerings?”

Long did she stand, and to this day I know not what her answer would have been. But Gerald spoke.

“No,” he said. “I suppose you have right, Ospak . . . the right of your time, which is not mine.” He took my hand, and Helgi’s. His lips brushed Thorgunna’s cheek. Then he turned and walked out into the darkness.

———

I heard, later, that he went to earth with Thorvald Hallsson, the crofter of Humpback Fell, and did not tell his host what had happened. He must have hoped to go unnoticed until he could somehow get berth on an eastbound ship. But of course word spread. I remember his brag that in the United States folk had ways to talk from one end of the land to another. So he must have scoffed at us, sitting in our lonely steads, and not known how fast news would get around. Thorvald’s son Hrolf went to Brand Sealskin-Boots to talk about some matter, and mentioned the guest, and soon the whole western island had the tale.

Now, if Gerald had known he must give notice of a manslaying at the first garth he found, he would have been safe at least till the Thing met, for Hjalmar and his sons are sober men who would not needlessly kill a man still under the wing of the law. But as it was, his keeping the matter secret made him a murderer and therefore at once an outlaw. Hjalmar and his kin rode straight to Humpback Fell and haled him forth. He shot his way past them with the gun and fled into the hills. They followed him, having several hurts and one more death to avenge. I wonder if Gerald thought the strangeness of his weapon would unnerve us. He may not have understood that every man dies when his time comes, neither sooner nor later, so that fear of death is useless.

At the end, when they had him trapped, his weapon gave out on him. Then he took a dead man’s sword and defended himself so valiantly that Ulf Hjalmarsson has limped ever since. That was well done, as even his foes admitted. They are an eldritch breed in the United States, but they do not lack manhood.

When he was slain, his body was brought back. For fear of the ghost, he having maybe been a warlock, it was burned, and everything he had owned was laid in the fire with him. Thus I lost the knife he gave me. The barrow stands out on the moor, north of here, and folk shun it, though the ghost has not walked. Today, with so much else happening, he is slowly being forgotten.

And that is the tale, priest, as I saw it and heard it. Most men think Gerald Samsson was crazy, but I myself now believe he did come from out of time, and that his doom was that no man may ripen a field before harvest season. Yet I look into the future, a thousand years hence, when they fly through the air and ride in horseless wagons and smash whole towns with one blow. I think of this Iceland then, and of the young United States men come to help defend us in a year when the end of the world hovers close. Maybe some of them, walking about on the heaths, will see that barrow and wonder what ancient warrior lies buried there, and they may well wish they had lived long ago in this time, when men were free.

THE END