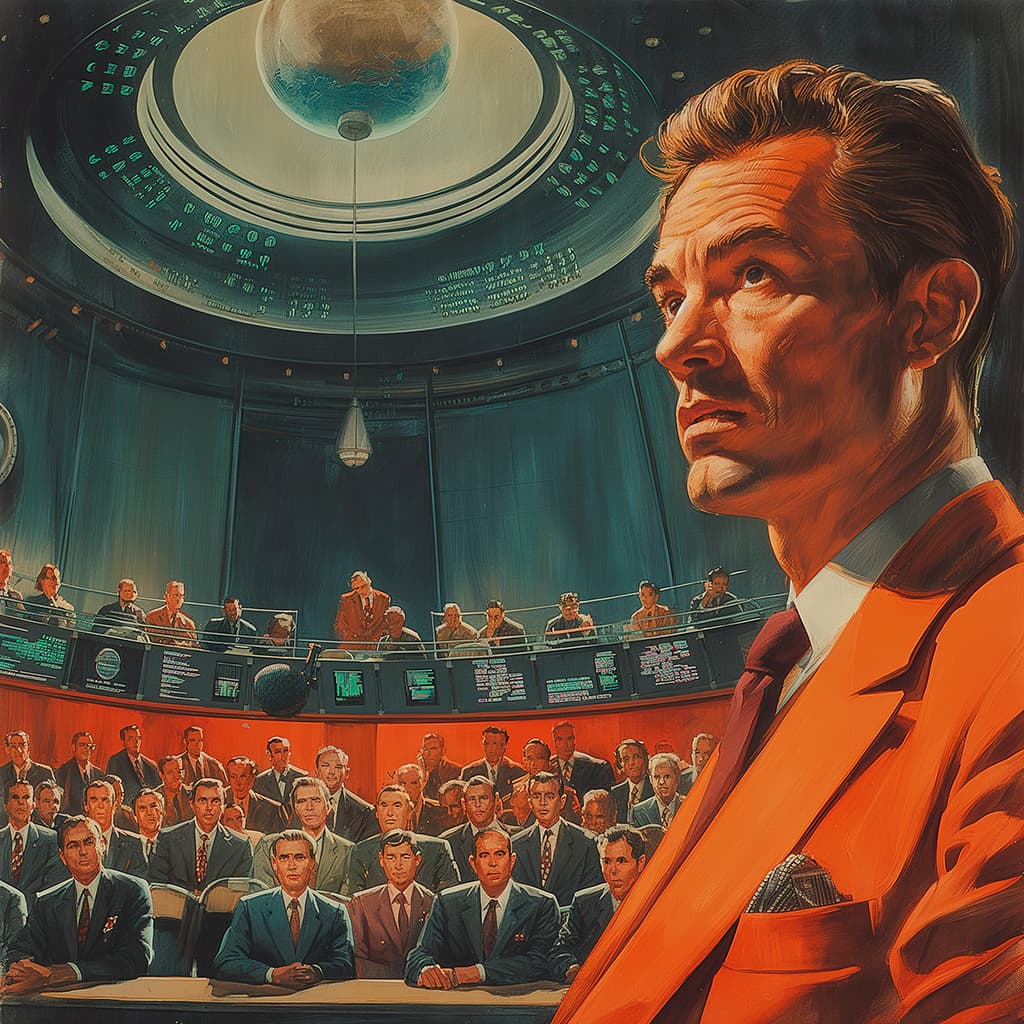

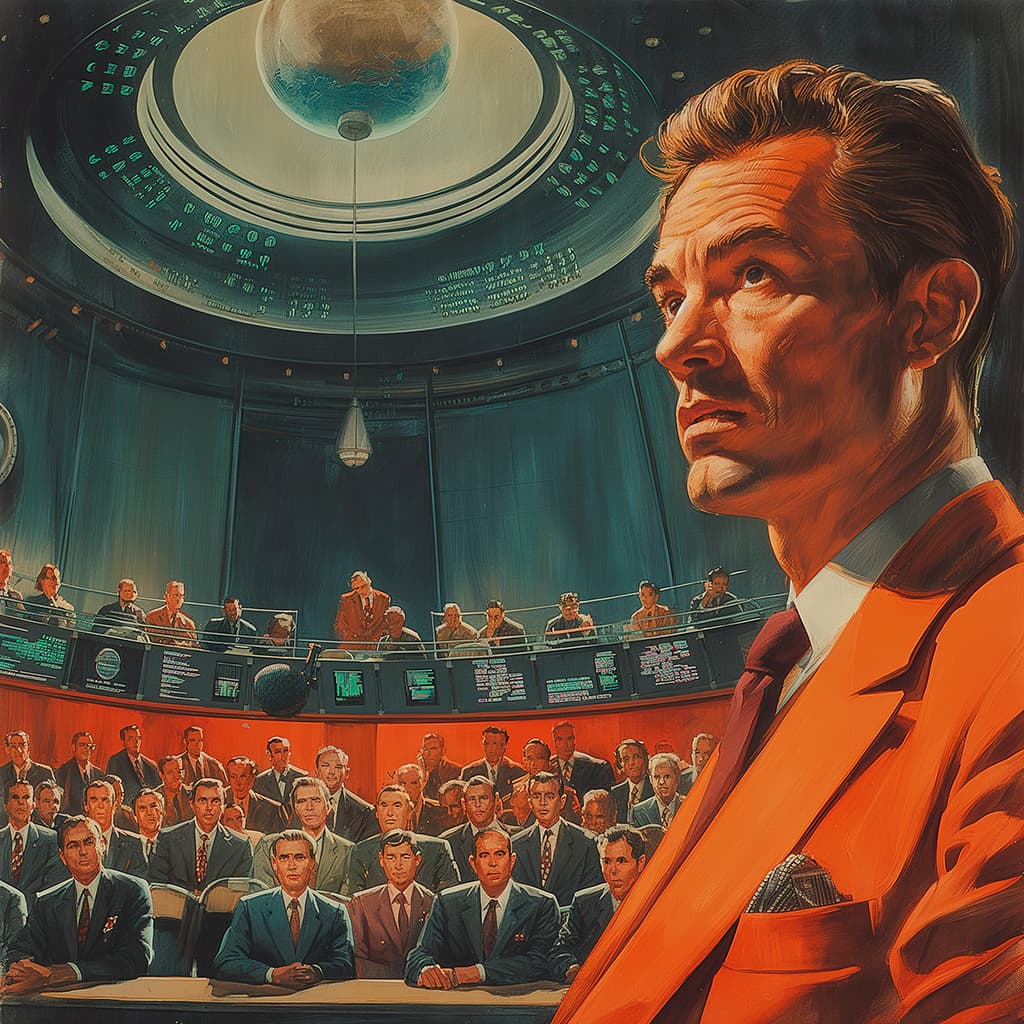

“The Food of the Gods,” a short story by Arthur C. Clarke published in 1964, revolves around human nutrition’s technological and ethical dilemmas. The protagonist is the CEO of a food company, who discusses the historical evolution of the human diet before a congressional committee, from the vicious dependence on meat and agricultural products to an innovative system of synthetic food production derived from essential elements. The need for efficiency and elimination of animal suffering has driven the transformation. In this process, a new product called Ambrosia Plus emerged, which took the market by storm and became the people’s favorite. However, this product hides a secret whose revelation will challenge its consumers.

The Food of the Gods

Arthur C. Clarke

(Full story)

It’s only fair to warn you, Mr. Chairman, that much of my evidence will be highly nauseating; it involves aspects of human nature that are very seldom discussed in public, and certainly not before a congressional committee. But I am afraid that they have to be faced; there are times when the veil of hypocrisy has to be ripped away, and this is one of them.

You and I, gentlemen, have descended from a long line of carnivores. I see from your expressions that most of you don’t recognize the term. Well, that’s not surprising—it comes from a language that has been obsolete for two thousand years. Perhaps I had better avoid euphemisms and be brutally frank, even if I have to use words that are never heard in polite society. I apologize in advance to anyone I may offend.

Until a few centuries ago, the favorite food of almost all men was meat—the flesh of once living animals. I’m not trying to turn your stomachs; this is a simple statement of fact, which you can check in any history book…

Why, certainly, Mr. Chairman, I’m quite prepared to wait until Senator Irving feels better. We professionals sometimes forget how laymen may react to statements like that. At the same time, I must warn the committee that there is very much worse to come. If any of you gentlemen are at all squeamish, I suggest you follow the Senator before it’s too late…

Well, if I may continue. Until modern times, all food fell into two categories. Most of it was produced from plants—cereals, fruits, plankton, algae, and other forms of vegetation. It’s hard for us to realize that the vast majority of our ancestors were farmers, winning food from land or sea by primitive and often backbreaking techniques; but that is the truth.

The second type of food, if I may return to this unpleasant subject, was meat, produced from a relatively small number of animals. You may be familiar with some of them—cows, pigs, sheep, whales. Most people—I am sorry to stress this, but the fact is beyond dispute—preferred meat to any other food, though only the wealthiest were able to indulge this appetite. To most of mankind, meat was a rare and occasional delicacy in a diet that was more than ninety-per-cent vegetable.

If we look at the matter calmly and dispassionately—as I hope Senator Irving is now in a position to do—we can see that meat was bound to be rare and expensive, for its production is an extremely inefficient process. To make a kilo of meat, the animal concerned had to eat at least ten kilos of vegetable food—very often food that could have been consumed directly by human beings. Quite apart from any consideration of aesthetics, this state of affairs could not be tolerated after the population explosion of the twentieth century. Every man who ate meat was condemning ten or more of his fellow humans to starvation…

Luckily for all of us, the biochemists solved the problem; as you may know, the answer was one of the countless by-products of space research. All food—animal or vegetable—is built up from a very few common elements. Carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, traces of sulphur and phosphorus—these half-dozen elements, and a few others, combine in an almost infinite variety of ways to make up every food that man has ever eaten or ever will eat. Faced with the problem of colonizing the Moon and planets, the biochemists of the twenty-first century discovered how to synthesize any desired food from the basic raw materials of water, air, and rock. It was the greatest, and perhaps the most important, achievement in the history of science. But we should not feel too proud of it. The vegetable kingdom had beaten us by a billion years.

The chemists could now synthesize any conceivable food, whether it had a counterpart in nature or not. Needless to say, there were mistakes—even disasters. Industrial empires rose and crashed; the switch from agriculture and animal husbandry to the giant automatic processing plants and omniverters of today was often a painful one. But it had to be made, and we are the better for it. The danger of starvation has been banished forever, and we have a richness and variety of food that no other age has ever known.

In addition, of course, there was a moral gain. We no longer murder millions of living creatures, and such revolting institutions as the slaughterhouse and the butcher shop have vanished from the face of the Earth. It seems incredible to us that even our ancestors, coarse and brutal though they were, could ever have tolerated such obscenities.

And yet—it is impossible to make a clean break with the past. As I have already remarked, we are carnivores; we inherit tastes and appetites that have been acquired over a million years of time. Whether we like it or not, only a few years ago some of our great-grandparents were enjoying the flesh of cattle and sheep and pigs—when they could get it. And we still enjoy it today. …

Oh dear, maybe Senator Irving had better stay outside from now on. Perhaps I should not have been quite so blunt. What I meant, of course, was that many of the synthetic foods we now eat have the same formula as the old natural products; some of them, indeed, are such exact replicas that no chemical or other test could reveal any difference. This situation is logical and inevitable; we manufacturers simply took the most popular presynthetic foods as our models, and reproduced their taste and texture.

Of course, we also created new names that didn’t hint of an anatomical or zoological origin, so that no one would be reminded of the facts of life. When you go into a restaurant, most of the words you’ll find on the menu have been invented since the beginning of the twenty-first century, or else adapted from French originals that few people would recognize. If you ever want to find your threshold of tolerance, you can try an interesting but highly unpleasant experiment. The classified section of the Library of Congress has a large number of menus from famous restaurants—yes, and White House banquets—going back for five hundred years. They have a crude, dissecting-room frankness that makes them almost unreadable. I cannot think of anything that reveals more vividly the gulf between us and our ancestors of only a few generations ago…

Yes, Mr. Chairman—I am coming to the point; all this is highly relevant, however disagreeable it may be. I am not trying to spoil your appetites; I am merely laying the groundwork for the charge I wish to bring against my competitor, Triplanetary Food Corporation. Unless you understand this background, you may think that this is a frivolous complaint inspired by the admittedly serious losses my firm has sustained since Ambrosia Plus came on the market.

New foods, gentlemen, are invented every week. It is hard to keep track of them. They come and go like women’s fashions, and only one in a thousand becomes a permanent addition to the menu. It is extremely rare for one to hit the public fancy overnight, and I freely admit that the Ambrosia Plus line of dishes has been the greatest success in the entire history of food manufacture. You all know the position: everything else has been swept off the market.

Naturally, we were forced to accept the challenge. The biochemists of my organization are as good as any in the solar system, and they promptly got to work on Ambrosia Plus. I am not giving away any trade secrets when I tell you that we have tapes of practically every food, natural or synthetic, that has ever been eaten by mankind—right back to exotic items that you’ve never heard of, like fried squid, locusts in honey, peacocks’ tongues, Venusian polypod…Our enormous library of flavors and textures is our basic stock in trade, as it is with all firms in the business. From it we can select and mix items in any conceivable combination; and usually we can duplicate, without too much trouble, any product that our competitors put out.

But Ambrosia Plus had us baffled for quite some time. Its protein-fat breakdown classified it as a straightforward meat, without too many complications—yet we couldn’t match it exactly. It was the first time my chemists had failed; not one of them could explain just what gave the stuff its extraordinary appeal—which, as we all know, makes every other food seem insipid by comparison. As well it might…but I am getting ahead of myself.

Very shortly, Mr. Chairman, the president of Triplanetary Foods will be appearing before you—rather reluctantly, I’m sure. He will tell you that Ambrosia Plus is synthesized from air, water, limestone, sulphur, phosphorus, and the rest. That will be perfectly true, but it will be the least important part of the story. For we have now discovered his secret—which, like most secrets, is very simple once you know it.

I really must congratulate my competitor. He has at last made available unlimited quantities of what is, from the nature of things, the ideal food for mankind. Until now, it has been in extremely short supply, and therefore all the more relished by the few connoisseurs who could obtain it. Without exception, they have sworn that nothing else can remotely compare with it.

Yes, Triplanetary’s chemists have done a superb technical job. Now you have to resolve the moral and philosophical issues. When I began my evidence, I used the archaic word “carnivore.” Now I must introduce you to another: I’ll spell it out the first time:

C-A-N-N-I-B-A-L…

(May 1961)