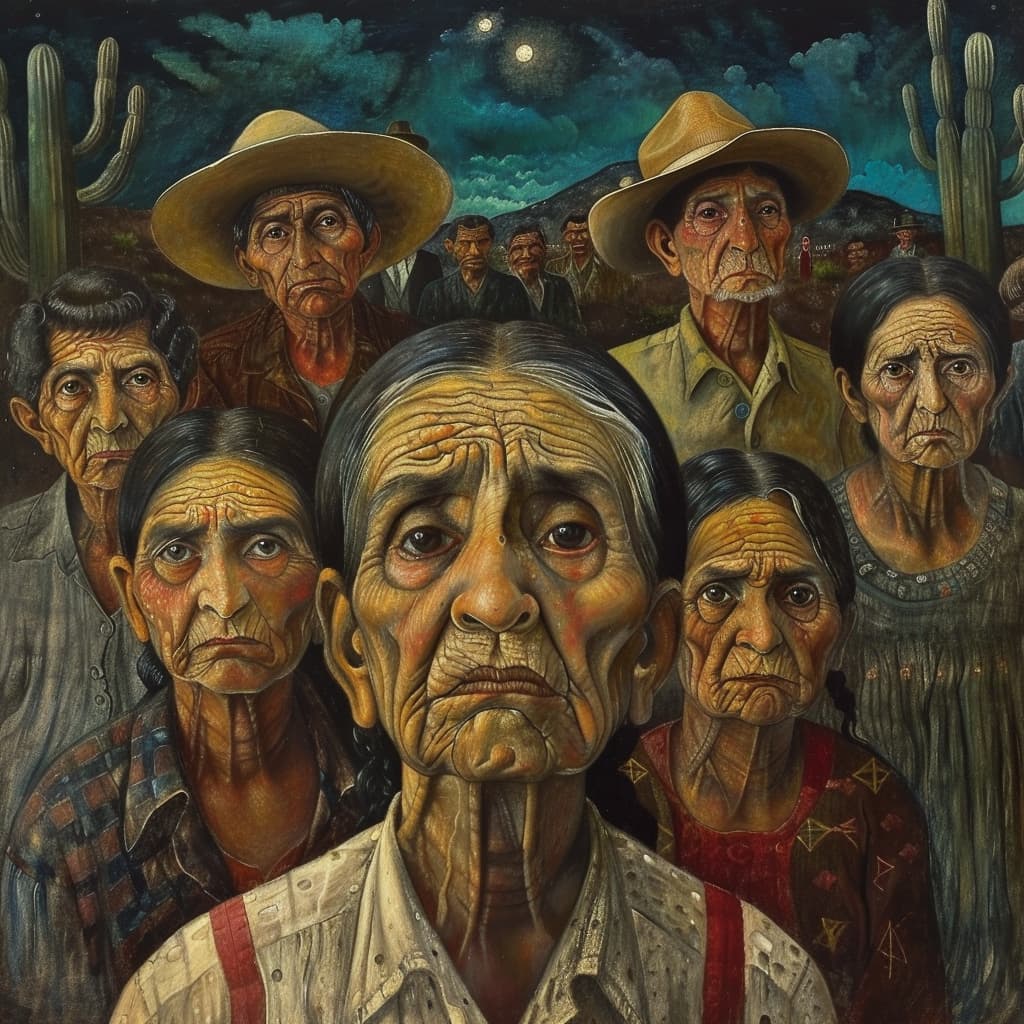

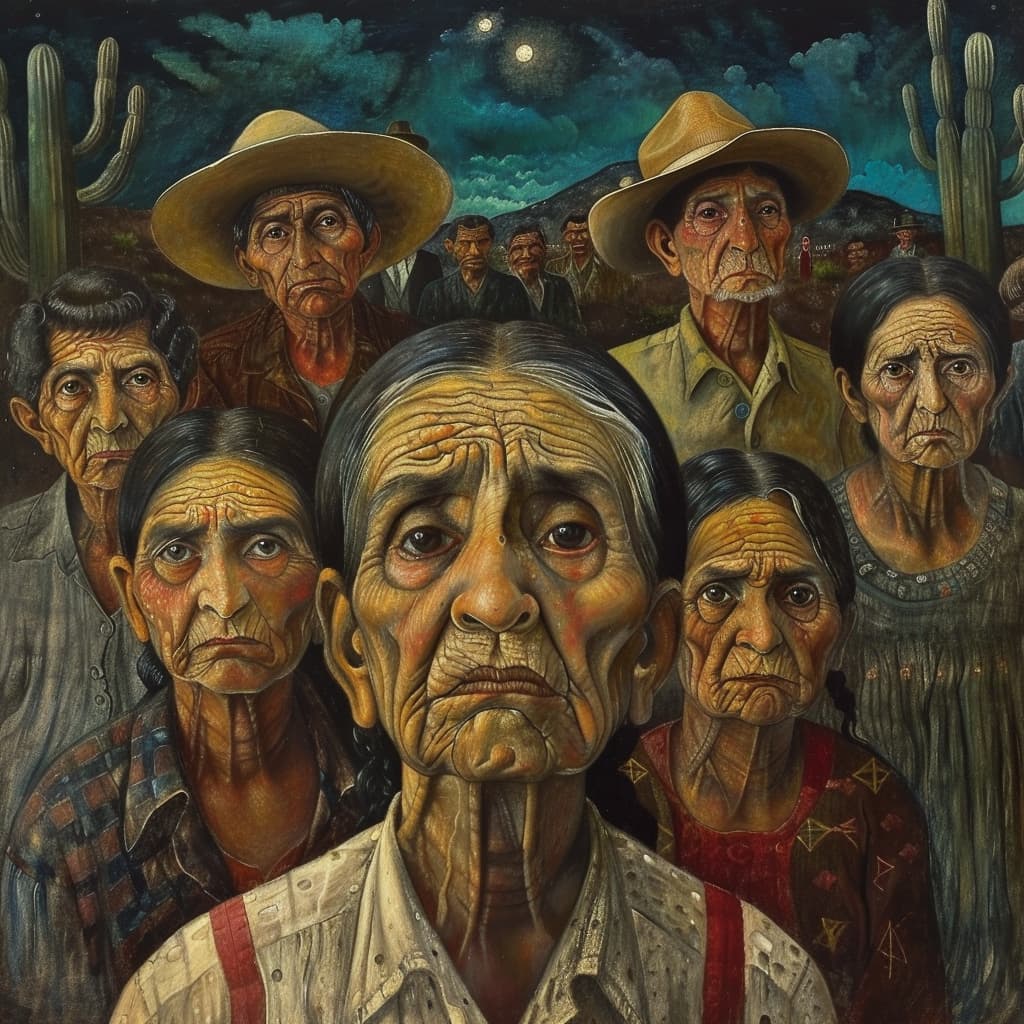

Synopsis: In “Luvina,” a story published in El llano en llamas (1953), Juan Rulfo describes an inhospitable village lashed by the constant wind and the aridity of its surroundings. Through the memories of a man who narrates his experience in it, a place is presented where nature and time seem to have stopped, leaving only the echo of loneliness and sadness. The inhabitants, marked by resignation, live a hard and monotonous life tied to the barren land and the weight of their dead. In the middle of this desolate landscape, the narrator shares his melancholy reflection on the futile struggle against an implacable destiny.

Luvina

by Juan Rulfo

(Full story)

Of all the high ranges in the south, the one in Luvina is the highest and rockiest. It’s full of that gray stone from which they make lime, but in Luvina they don’t make lime from it nor do they put it to any good use. They call it crude stone there, and the incline that rises toward Luvina is called Crude Stone Hill. The wind and sun have taken care of breaking it down, so the earth around there is white and shining, as if it were bedewed with morning dew; though all this is just words, because in Luvina the days are as cold as the nights and the dew grows thick in the sky before it manages to reach the earth.

. . . And the earth is steep. It slashes everywhere into deep ravines, so far down that they disappear, that’s how far down they go. People in Luvina say dreams rise out of those ravines; but the only thing I ever saw rise up from there was the wind, whirling, as if it had been imprisoned down below in reed pipes. A wind that doesn’t even let bittersweet grow: those sad little plants can barely live, holding on for all they’re worth to the side of the cliffs in these hills, as if they were smeared onto the earth. Only at times, where there’s a little shade, hidden among the rocks, can the chicalote bloom with its white poppies. But the chicalote soon withers. Then one hears it scratching the air with its thorny branches, making a noise like a knife on a whetstone.

“You’ll see that wind blowing over Luvina. It’s gray. They say that’s because it carries volcanic sand; but the truth is, it’s a black air. You’ll see. It settles on Luvina, clinging to things as if it were biting them. And on many days it carries off the roofs of houses as if it were carrying off a straw hat, leaving the walls unprotected and bare. Then it scratches, as if it had nails: one hears it morning and night, hour after hour, without rest, scraping the walls, tearing off strips of soil, gouging under the doors with its pointy spade, until one feels it roiling inside oneself, as if it were trying to rattle the hinges of our very bones. You’ll see.”

The man who was talking remained quiet for a while, looking outside.

The sound of the river passing its rising waters over the camichín boughs reached them; the rumor of the air softly moving the almond-tree leaves, and the screams of the children playing in the little space illuminated by the light coming out of the store.

Termites came in and bounced against the oil lamp, falling to the ground with their wings scorched. And night still advanced outside.

“Hey, Camilo, give us two more beers!” the man went on. Then he added:

“Something else, señor. In Luvina you’ll never see a blue sky. The whole horizon is colorless; always cloudy with a caliginous stain that never disappears. The whole ridge bald, without a single tree, without a single green thing for your eyes to rest on; everything enveloped in the ash-cloud of lime. You’ll see: those hills, their lights darkened as if they were dead, and Luvina at the very top, crowning it with its white houses as if it were the crown of a dead man . . .”

The children’s screams got closer until they were inside the store. That made the man stand up, go to the door, and say to them: “Get away from here! Stop interrupting! Go on playing, but without making a ruckus.”

Then, heading back to the table, he sat down and said:

“So yes, as I was saying. It rains very little there. By midyear a bunch of storms arrive and lash the earth, ripping it up, leaving nothing but a sea of stones floating on the crust. Then it’s nice to see how the clouds crawl along, the way they wander from one hill to another making noise as if they were swollen bladders; ricocheting and thundering just as if they were breaking apart on the edge of the ravines. But after ten or twelve days they leave and don’t come back until the following year, and sometimes it happens they don’t come back for a few years . . .

“. . . Yes, rain is scarce. Little or next to nothing, to the point that the earth, in addition to being dry and shrunken like old leather, is full of cracks and that thing they call “pasojos de agua” there, which are nothing but dirt clods hardened into sharp-edged stones that pierce your feet when you walk, as if the land itself had grown thorns there. As if it were like that.”

He drank the beer until only foam bubbles were left in the bottle and then went on talking:

“No matter how you look at it, Luvina is a very sad place. Now that you’re going there, you’ll see what I mean. I would say it’s the place where sadness nests. Where smiles are unknown, as if everyone’s faces had gone stiff. And, if you want, you can see that sadness at every turn. The wind that blows there stirs it up but never carries it away. It’s there, as if it had been born there. You can even taste it and feel it, because it’s always on you, pressed against you, and because it’s oppressive like a great poultice on your heart’s living flesh.

“. . . People there say that when the moon is full, they see the shape of the figure of the wind wandering the streets of Luvina, dragging a black blanket; but the thing I always came to see, when the moon was out in Luvina, was the image of despair . . . always.

“But drink your beer. I see you haven’t even tried it. Drink. Or perhaps you don’t like it as it is, at room temperature. There’s no other option here. I know it tastes bad like that; that it takes on a flavor like donkey’s pee. You get used to it around here. Keep in mind that over there you can’t even get this. You’ll miss it when you get to Luvina. Over there you won’t be able to get anything but mescal, which people make with an herb called hojasé, and after the first few swallows you’ll be going round and round as if you had been beaten up. Better drink your beer. I know what I’m talking about.”

Outside you could still hear the river struggle. The rumor of wind. Children playing. It seemed as if it were still early in the night.

Once again the man had gone to look out the door and had come back. Now he was saying:

“It’s easy to look at things from over here, merely recalled from memory, where there’s no similarity. But I have no problem going on telling you what I know in regard to Luvina. I lived there. I left my life there . . . I went to that place with my illusions intact and came back old and used up. And now you’re going there . . . All right. I seem to remember the beginning. I put myself in your shoes and think . . . Look, when I first got to Luvina . . . But first can I have your beer? I see you’re not paying any attention to it. And it’ll be good for me. It’s healing for me. I feel as if my head were being rinsed with camphor oil . . . Well, as I was telling you, when I first arrived in Luvina, the mule driver that took us there didn’t even want the beasts to rest. As soon as we were on the ground, he turned around:

“ ‘I’m going back,’ he said.

“ ‘Wait, you won’t let your animals take a rest? They’re beaten up.’

“ ‘They would end up even more messed up here,’ he said. ‘I better get back.’

“And he left, dropping us at Crude Stone Hill, spurring his horses as if he were fleeing from a place of the devil.

“We, my wife and three children, remained there, standing in the middle of the plaza, with all our belongings in our arms. In the middle of that place where you heard only the wind . . .

“Nothing but the plaza, without a single plant to break the wind. We stayed there.

“Then I asked my wife:

“ ‘What country are we in, Agripina?’

“And she shrugged her shoulders.

“ ‘Well, if you don’t mind, go look for someplace to eat and someplace to spend the night. We’ll wait for you here,’ I said to her.

“She took the youngest of our children and left. But she didn’t come back.

“At dusk, when the sun lit up only the hilltops, we went looking for her. We walked along the narrow streets of Luvina, until we found her inside the church: sitting right in the middle of that lonely church, with the child asleep between her legs.

“ ‘What are you doing here, Agripina?’

“ ‘I came in to pray,’ she said to us.

“ ‘What for?’ I asked.

“She shrugged her shoulders.

“There was nothing to pray to there. It was an empty shack, with no doors, just some open galleries and a broken ceiling through which the air filtered like a sieve.

“ ‘Where’s the inn?’

“ ‘There is no inn.’

“ ‘And the hostel?’

“ ‘There is no hostel.’

“ ‘Did you see anyone? Does anyone live here?’ I asked her.

“ ‘Yes, right opposite . . . Some women . . . I can still see them. Look, behind the cracks in that door I see the eyes watching us, shining . . . They have been staring at us . . . Look at them. I see the shining balls of their eyes . . . But they have nothing to give us to eat. Without even sticking their heads out, they told me there’s no food in this town . . . Then I came here to pray, to ask God on our behalf.’

“ ‘Why didn’t you come back? We were waiting for you.’

“ ‘I came here to pray. I haven’t finished yet.’

“ ‘What country is this, Agripina?’

“And she shrugged her shoulders again.

“That night we settled down to sleep in a corner of the church, behind the dismantled altar. Even there you could feel the wind, though not quite as strong. We kept hearing it passing above us, with its long howls; we kept hearing it coming in and going out through the hollow concavities of the doors; hitting the crosses in the stations of the cross with its hands of wind: big, strong crosses made of mesquite wood that hung from the walls over the length of the church, tied with wires that grated each time the wind shook them as if it were the grating of teeth.

“The children were crying because they were too frightened to sleep. And my wife was trying to hold them all in her arms. Hugging her bouquet of children. And I was there, not knowing what to do.

“The wind calmed down a bit before sunrise. Later on it came back. But there was a moment at dawn when everything became still, as if the sky and the earth had joined together, crushing all sounds with their weight . . . You could hear the children breathing, now more relaxed. I could hear my wife breathing heavily next to me:

“ ‘What’s that?’ she said to me.

“ ‘What’s what?’ I asked her.

“ ‘That. That noise.’

“ ‘It’s silence. Go to sleep. Rest, even if only a little bit, because it will be dawn soon.’

“But soon I heard it, too. It was like bats flitting in the darkness, very close to us. Like bats with their long wings sweeping against the floor. I got up and the sounds of wings beating became stronger, as if the colony of bats had been frightened and they were flying toward the holes in the doors. Then I tiptoed over there, feeling that muffled whispering in front of me. I stopped in the doorway and I saw them. I saw all the women of Luvina with water jugs on their shoulders, with their shawls hanging from their heads and their dark silhouettes against the black depths of the night.

“ ‘What do you want?’ I asked them. ‘What are you looking for at this time of night?’

“One of them responded:

“ ‘We’re going to get water.’

“I saw them standing in front of me, watching me. Then, as if they were shadows, they started walking down the street with their black water jars.

“No, I’ll never forget that first night I spent in Luvina.

“. . . Don’t you think this deserves another drink? If only so I can get rid of the bad taste of the memory.”

“I believe you asked me how many years I was in Luvina, right? . . . Truth is, I don’t know. I lost any sense of time once the fever got me all turned around; but it must have been an eternity . . . And that’s because time is very long there. No one keeps count of hours, nor is anyone interested in how the years mount up. Days start and end. Then night comes. Just day and night until the day you die, which for them is a kind of hope.

“You must think I’m harping on the same idea. And yes, it’s true, señor . . . To sit on the doorstep, watching the sun rise and set, raising and lowering your head, until the springs go slack and then everything comes to a halt, without time, as if one lived forever in eternity. That’s what the old men do over there.

“Because only old people live in Luvina and those who aren’t yet born, as people say . . . And women with no strength, just skin and bones, they’re so thin. The children who were born there have left . . . No sooner do they see the light of dawn than they become men. As people say, they jump from their mother’s breast to the hoe and they disappear from Luvina. That’s how things are there.

“Only very old men remain and abandoned women, or women with a husband who is God only knows where . . . They return every so often like the storms I was telling you about; you can hear the whole town whispering when they come back and something like a grunt when they leave . . . They leave behind a sack of provisions for the old and plant another child in their wife’s womb, and then no one knows anything about them again until next year, and sometimes never . . . That’s the custom. Over there it’s called the law, but it’s the same thing. Their children spend their lives working for their parents the way they did for theirs and as who knows how many before them behaved in accordance with that law . . .

“Meanwhile, the old people wait for them and for the day of their death, sitting in their doorways, with their arms at their sides, moved only by the grace that is a child’s gratitude . . . Alone, in that solitude of Luvina.

“One day I tried convincing them to go elsewhere, where the soil was good. ‘Let’s leave this place,’ I said. ‘We’ll find a way to settle somewhere else. The government will help us.’

“They listened to me without batting an eye, looking at me from the depths of their eyes, from which only a little light emerges from deep inside.

“ ‘You say the government will help us, professor? Are you acquainted with the government?’

“I told them I was.

“ ‘We know it, too. It so happens that we do. What we know nothing about is the government’s mother.’

“I told them it was the fatherland. They shook their heads to say no. And they laughed. It was the only time I saw the people from Luvina laugh. They bared their ruined teeth and told me no, the government had no mother.

“And you know what? They’re right. The government man only remembers them when one of his young men has done something wrong down here. Then he sends to Luvina for him and they kill him. Beyond that, they don’t even know that they exist.

“ ‘You want to tell us we should leave Luvina because, according to you, it’s enough being hungry with no need to be,’ they said to me. ‘But if we leave, who’ll carry our dead? They live here and we can’t leave them behind.’

“And they’re still there. You’ll see them once you get there. Chewing dry mesquite pulp and swallowing their saliva in order to outwit hunger. You’ll see them passing by like shadows, hugging the walls of houses, almost dragged along by the wind.

“ ‘Don’t you hear that wind?’ I finally told them. ‘It’ll be the end of you.’

“ ‘You endure what you have to endure. It’s God’s mandate,’ they answered me. ‘It’s bad when the wind stops blowing. When that happens, the sun presses close to Luvina and sucks our blood and the little water we have in our hides. The wind makes the sun stay up there. It’s better that way.’

“I said nothing more. I left Luvina and I haven’t gone back nor do I think I will.

“. . . But look at the somersaults the world is doing. You’re going there now, in a few hours. It’s probably fifteen years since I was told the same thing: ‘You’re going to San Juan Luvina.’

“In those days I was strong. I was full of ideas . . . You know that ideas infuse us all. And one goes with a burden on one’s shoulders to make something out of one’s self. But it didn’t work out in Luvina. I did the experiment and it came undone . . .

“San Juan Luvina. The name sounded celestial to me. But it’s Purgatory. A moribund place where even the dogs have died and there’s not even anyone to bark at the silence; because the moment one gets used to the winds that blow there, one hears nothing but that silence that exists in all solitudes. And that uses you all up. Look at me. It used me up. You’re going, and you’ll understand what I’m saying very soon . . .

“What do you think if we ask that man to put together some mezcalitos for us? With beer one needs to get up all the time and that interrupts the conversation. Listen, Camilo, send us over some mezcals right away!

“So yes, as I was telling you . . .”

But he didn’t say anything. He kept staring at a fixed point on the table where the termites, now without wings, circled like naked little worms.

Outside one could hear the night advancing. The water of the river splashing against the trunks of the camichines. The already distant shouting of children. Through the small sky of the doorway one could see the stars.

The man who was watching the termites slumped over the table and fell asleep.

THE END