In “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” Ursula K. Le Guin presents a utopian city filled with joy, beauty, and prosperity, where citizens live in harmony and celebrate life’s pleasures. However, this idyllic society harbors a dark secret: the happiness of all depends on the perpetual suffering of a single, neglected child locked away in a small, filthy room. The citizens are aware of this cruel bargain, and while most accept it, a few individuals, unable to bear the moral cost, choose to leave the city, walking into the unknown. Through this thought-provoking parable, Le Guin explores themes of morality, sacrifice, and the ethical complexities of collective happiness.

Warning

The following summary and analysis is only a semblance and one of the many possible readings of the text. It is not intended to replace the experience of reading the story.

Summary of the short story The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas by Ursula K. Le Guin

“The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” by Ursula K. Le Guin begins with a depiction of the Festival of Summer in the radiant, idyllic city of Omelas. The story paints a picture of a city filled with joy and abundance. Its people, though happy, are not naive or simple; they live sophisticated lives filled with knowledge and maturity, free from the institutions and cruelties that mark other societies, such as kings, soldiers, or exploitative trade systems. The city is vibrant, with processions winding through the streets, children playing, and horses racing in the bright, sunlit meadows. There is music, laughter, and an overwhelming sense of celebration. However, despite this perfection, Le Guin subtly challenges the reader to consider the possibility of joy untainted by darkness, raising questions about the nature of happiness and morality.

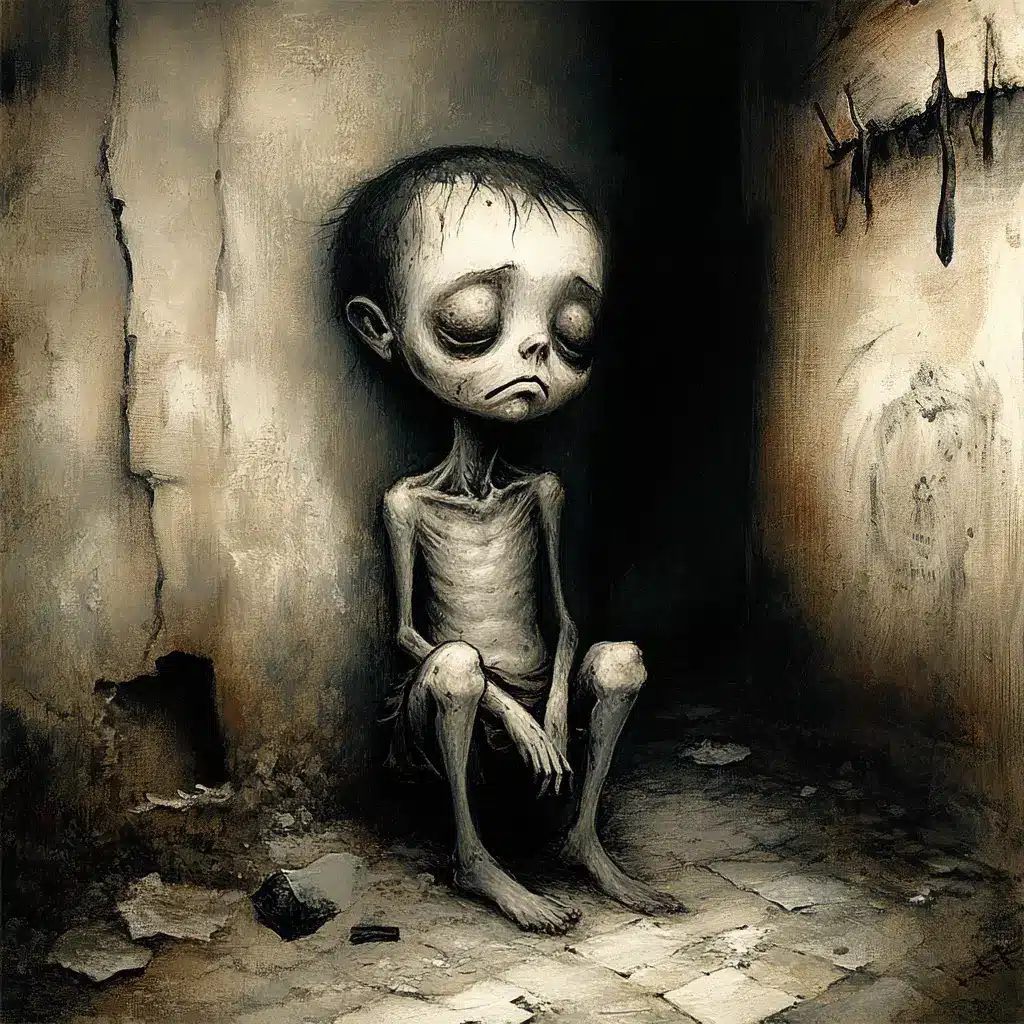

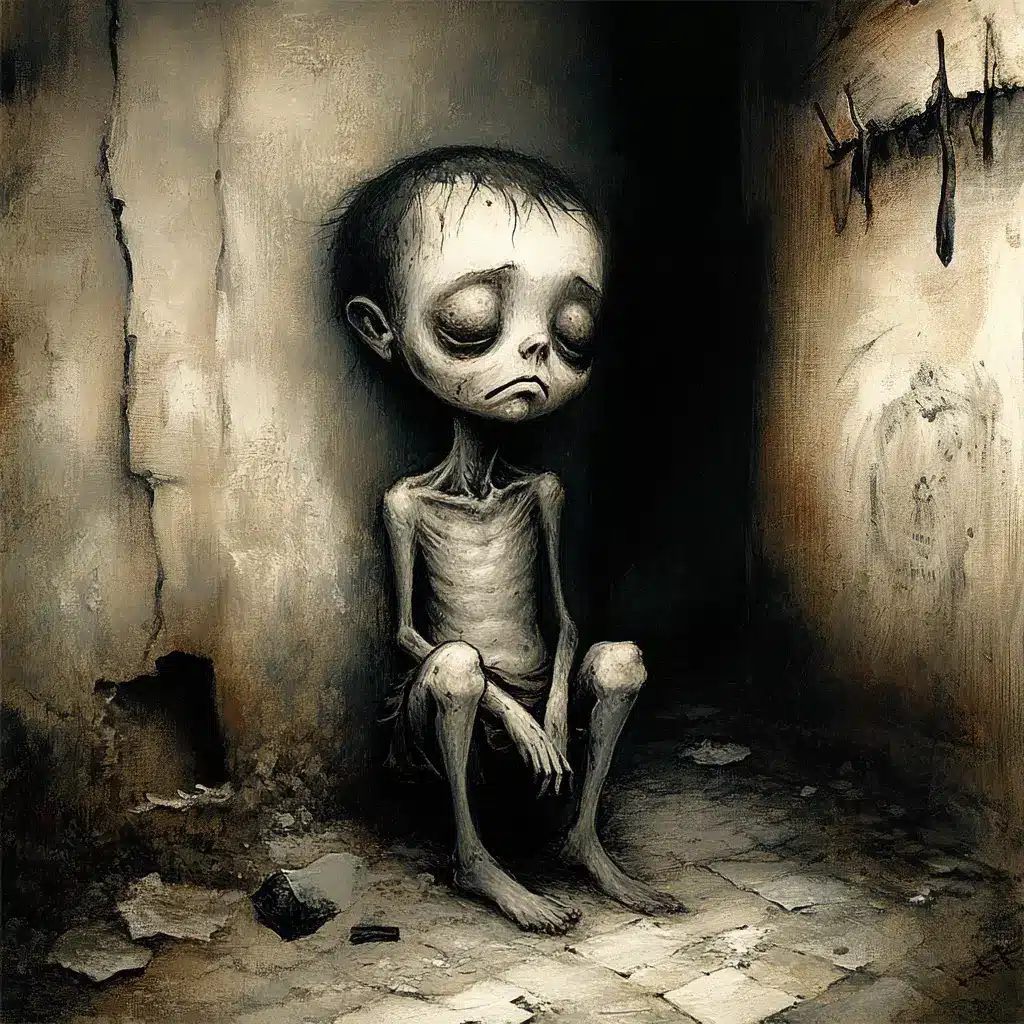

Beneath this surface of utopian bliss, however, lies a harrowing secret. In a small, locked room, hidden away from the splendor of Omelas, a child is imprisoned. This child, malnourished and terrified, lives in squalor, its body weakened by neglect and abuse. The child is kept in a constant state of misery, deprived of human contact and basic needs, and its existence is known to all the citizens of Omelas. The happiness, prosperity, and beauty of the city, as well as the well-being of its inhabitants, depend entirely on this child’s suffering. This terrible reality is explained to the citizens when they are young, and they come to understand that the child’s misery is the price of their own joy.

Although many are horrified when they first learn of the child’s plight, they ultimately accept the situation as necessary. Some visit the child to see for themselves, feeling disgust and anger. However, gradually, they come to terms with the paradox: their society’s perfect happiness can only exist through the suffering of this one helpless being. The reasoning behind this grim arrangement is that to free the child would bring ruin to Omelas, and the child itself, so broken and degraded, would not even find happiness in freedom.

Still, not everyone can live with this knowledge. Occasionally, young or old individuals choose to walk away from Omelas. These people leave the city silently and alone, traveling towards an uncertain destination, a place unknown and undescribed. Their departure is quiet and solitary, and they never return. The story leaves their fate unresolved, as it is impossible to say where they go or what they seek, but they cannot accept the moral bargain that sustains Omelas’ happiness.

In this haunting tale, Le Guin explores the complex and often uncomfortable relationship between happiness and suffering, asking the reader to confront the ethical dilemmas that lie beneath a seemingly perfect world.

Analysis of the short story The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas by Ursula K. Le Guin

Characters from the story The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas

In “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” traditional characters with names or individual backstories are absent. Instead, the story focuses on collective entities—the people of Omelas, the suffering child, and the ones who choose to leave. These “characters” symbolize various moral and philosophical ideas, and each group embodies a distinct reaction to society’s moral compromise.

The people of Omelas, as a collective, are the most prominent “characters” in the story. They are depicted as intelligent, mature, and joyful individuals who live in a utopian society filled with beauty and celebration. They are not barbaric or naïve; their happiness is portrayed as a conscious choice, a product of their wisdom and discernment. However, this same maturity is what allows them to accept the moral horror that sustains their way of life—the suffering of the child. As a group, they represent the moral complexity of societies that thrive on exploiting others. Their decision to rationalize the child’s misery as necessary for the greater good reflects a collective complicity that can be seen as a critique of how real-world societies often justify inequality and suffering for the sake of prosperity. Though the people are not cruel or sadistic, they embody the moral ambiguity of disregarding injustice for the sake of comfort.

The child in the locked room is the key secondary character, though it remains passive and voiceless throughout the story. This child is both a literal figure—a frail, suffering being—and a symbol of the hidden, unjust foundation on which Omelas’s happiness is built. The child’s physical condition is appalling: malnourished, filthy, and afraid; it has been reduced to a state of almost complete degradation. However, the child is not entirely without memory or consciousness. It remembers sunlight, its mother’s voice, and perhaps some semblance of happiness, deepening its current situation’s tragedy. The child’s suffering is kept out of sight, and yet it is the most essential part of the city’s moral and philosophical framework. In many ways, the child serves as a moral litmus test for the reader and the citizens of Omelas: whether to accept the child’s suffering as inevitable or to challenge the very foundation of the city’s prosperity.

Finally, there are the ones who walk away from Omelas—a smaller but significant group of individuals who choose to leave the city after learning of the child’s plight. They are never described in detail; the story does not provide their names, personalities, or even specific reasons for their departure. Yet their actions speak volumes. Unlike most Omelas citizens who learn to accept the terrible moral compromise, these individuals cannot reconcile their consciences with the child’s suffering. They refuse to participate in a society that is built on such a foundation, even though leaving Omelas means walking into an unknown future. These characters symbolize a moral stance that rejects complicity, no matter the cost. Their departure is quiet and solitary, which suggests that this choice is not made lightly. It is an act of personal integrity but also one of loneliness and uncertainty, as the place they head towards is left deliberately vague and possibly nonexistent. Their decision embodies the idea of moral courage and the difficult path of resisting societal norms when those norms are ethically indefensible.

In what setting does the story take place?

The setting of “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” is the city of Omelas, a fictional and idyllic place that seems almost utopian on the surface. Omelas is described as a beautiful coastal city with bright towers overlooking the sea and surrounded by natural splendor. The setting is introduced during the Festival of Summer, a time of celebration and joy, where the streets are filled with processions of people, music, and dance. The city is vibrant, with its red-roofed houses, lush gardens, and trees lined with trees. The setting is one of abundance and harmony, with the sounds of bells ringing out over the city and banners snapping in the breeze. The people of Omelas, who are joyful and content, embody the city’s spirit, which appears to be a place free from conflict, oppression, or hardship.

Nature plays a significant role in this setting. Beyond the city’s boundaries lie vast green meadows called the “Green Fields,” where much of the Festival of Summer occurs. These meadows are expansive, filled with light and life, and serve as the backdrop for the horse races and gatherings of youths. The surrounding mountains in the distance, capped with snow, enhance the sense of natural beauty and serenity. This landscape is painted to feel almost too perfect, like something out of a dream. The morning air is clear and fresh, the colors vivid and warm, and the overall atmosphere is one of peaceful celebration.

However, this outward perfection hides a darker, hidden part of Omelas that drastically shifts the tone of the setting. Beneath one of the city’s grand public buildings or within a private home lies a tiny, locked room in a basement. In stark contrast to the beauty and openness of the city above, this room is cramped, dirty, and oppressive. It is described as a damp, filthy space, barely large enough for the child who is kept imprisoned there. The light that enters is faint and dusty, only seeping through cracks. The room’s atmosphere is suffocating, marked by the stench of neglect and the presence of grimy mops and a rusty bucket. This hidden, nightmarish room is a direct counterpoint to the city’s brightness and serves as the setting for the most critical and unsettling aspect of Omelas’ existence: the suffering child.

The duality of these settings—the radiant, joyous city above and the dark, squalid room below—reflects the story’s moral complexity. The beauty of Omelas is dependent on the horror hidden in its depths. The setting is not just a backdrop but a crucial element in the story’s exploration of moral sacrifice and complicity. Omelas, as a city, is both a utopia and a dystopia, depending on which part of it one chooses to focus on. Its stunning landscapes and joyous festivals create an almost surreal sense of perfection, but the existence of the locked room forces the reader to reconsider this beauty and question the ethical foundation upon which it rests.

Ultimately, the setting of Omelas is deliberately constructed to engage the reader’s imagination. Le Guin encourages us to envision the city in ways that suit our own interpretations of happiness and perfection, allowing us to add or subtract elements that we believe would fit into such a place. This flexibility in depicting the city makes the moral dilemma at the heart of the story even more poignant, as it asks us to consider how far we are willing to go to preserve an ideal society and at what cost.

Who narrates the story?

The narrator in “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” is a unique and highly distinctive presence, blending first-person and third-person perspectives to create an intimate, conversational tone. The narrator is not a character in the story but rather an observer who speaks directly to the reader, guiding them through the description of Omelas and engaging them in the moral and philosophical questions at the story’s heart. This narrative style is unusual because it breaks the traditional barrier between the storyteller and the audience, drawing readers into creating the setting and the ethical dilemmas it presents.

The narrator is omniscient in many ways, offering detailed descriptions of Omelas and its people while also having insight into the city’s inner workings and the suffering child’s underlying secret. However, despite this omniscience, the narrator admits to a certain level of uncertainty or incompleteness in describing the city. They frequently acknowledge that Omelas may be difficult to believe in, often asking rhetorical questions such as “Do you believe?” or suggesting ways the reader might envision the city differently if it helps make the image more convincing. For example, when discussing whether Omelas has advanced technology or if it needs something like an orgy to make it more credible, the narrator invites the reader to imagine these details however they like, as if the reader’s preferences partly shape the story’s world.

This interactive quality of the narration allows the narrator to become a co-creator of the setting alongside the reader. The narrator openly admits to struggling with describing happiness in a believable and not simplistic way; by doing so, they invite the reader into the process of imagining Omelas. This self-awareness makes the narrator seem reflective, philosophical, and deeply concerned with the larger ethical implications of the story rather than just recounting events. It’s as though the narrator is wrestling with the same questions they pose to the reader—about joy, morality, and the cost of happiness—without presenting easy answers.

Furthermore, the narrator’s tone shifts from joyful and celebratory in the early parts of the story to somber and reflective when describing the child in the locked room. There is a clear sense that the narrator is grappling with the moral complexities of the situation, which gives the story a personal and urgent quality. This change in tone adds depth to the narrative, as it mirrors the shift in the reader’s own emotional response—from admiration for the utopian beauty of Omelas to shock and discomfort at the hidden suffering that sustains it.

In the final part of the story, when the narrator discusses those who choose to walk away from Omelas, the narration takes on a more mysterious and uncertain quality. The narrator admits to not knowing where these individuals go or what lies beyond Omelas, which leaves the story open-ended. This ambiguity is central to the narrator’s role, as they do not offer clear moral judgments but instead leave space for the reader to reflect and decide for themselves what to make of the situation.

In summary, the narrator in “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” is an omniscient yet conversational guide who blends philosophical reflection with vivid description. Their role is not merely to tell the story but to engage the reader in a deeper inquiry into the ethical questions the story raises. The narrator’s openness, self-awareness, and direct address to the reader create a unique and thought-provoking narrative voice that compels the reader to participate in the moral dilemmas at the heart of Omelas.

What themes does the story develop?

One of the central themes in “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” is the moral cost of happiness. The story presents a seemingly perfect society where all the citizens enjoy lives of joy, abundance, and peace. However, this happiness is built upon the misery of a single child, who is kept in squalor and torment. The existence of this suffering child raises profound ethical questions: Can happiness truly be just if it depends on the suffering of even one innocent person? Omelas’ citizens must confront this question and decide whether to accept or reject the bargain. The theme forces readers to consider the hidden costs of their own happiness and privilege, particularly in societies where the suffering of the few may be overlooked for the comfort of the many. The child’s misery, while hidden, becomes a symbol of the ethical compromises often made in the pursuit of societal well-being.

Closely related to this is the theme of utilitarianism and ethical justification. Utilitarianism is the philosophical idea that actions should be judged based on their ability to produce the greatest good for the greatest number of people. In Omelas, this principle is taken to an extreme, where the happiness of the entire city is maintained at the expense of one suffering child. The citizens justify this arrangement because the child’s release would destroy the happiness of thousands, and thus, they rationalize the sacrifice of one for the benefit of many. This moral dilemma highlights the limits of utilitarian thinking—at what point does the suffering of one individual become too high a price for the collective good? The story questions whether such trade-offs can ever be morally justified, and it challenges the reader to examine the ethical consequences of sacrificing individual well-being for the greater societal good.

Another significant theme is the individual’s response to societal injustice. The story presents three distinct responses to the suffering of the child. Most citizens of Omelas accept the situation after grappling with its moral complexity, rationalizing it as necessary to preserve their society. Though it troubles them, they choose to live with the knowledge of the child’s misery. However, a smaller group of individuals who walk away cannot reconcile themselves to this injustice and choose to leave Omelas, heading into an unknown and possibly nonexistent future. This theme explores how individuals respond to injustice: some may choose to accept it, others may turn away, and others may take direct action. Walking away is not framed as heroic or triumphant, but it represents a refusal to be complicit in a system that requires suffering. The story delves into the tension between personal conscience and societal norms, asking what rejecting or resisting a fundamentally unjust system means, even when resistance means isolation and uncertainty.

The story also explores the themes of complicity and moral responsibility. The citizens of Omelas are not actively inflicting harm on the child, but their passive acceptance of the child’s suffering makes them complicit in maintaining the system. This complicity is not based on direct cruelty but on a willful ignorance or rationalization of the injustice that enables their lives to flourish. The theme suggests that in many societies, individuals may benefit from systems of exploitation or inequality, even if they are not directly responsible for them. The citizens’ varying degrees of complicity—ranging from those who ignore the child’s existence to those who visit the child and weep—underscore the uncomfortable reality that moral responsibility is not limited to those who commit overt acts of harm but extends to those who allow injustice to persist. The story challenges readers to reflect on their own lives and the ways in which they might be complicit in the suffering of others, even indirectly.

Lastly, there is the theme of freedom and escape. The ones who walk away from Omelas represent a rejection of society’s moral and ethical compromises, choosing to abandon it rather than live with the knowledge of the child’s suffering. Their departure, however, is not described as an act of rebellion or defiance; it is a quiet, individual decision to seek something beyond the moral confines of Omelas. Yet the destination of these individuals is unknown—Le Guin never specifies where they go or whether this place even exists. This ambiguity raises questions about the nature of freedom and what it means to escape an unjust system. Do the ones who walk away find a better life, or do they choose isolation and uncertainty over compromised happiness? The theme of escape suggests that true freedom might lie in the refusal to accept injustice, but it also hints at the loneliness and uncertainty accompanying such a choice.

What writing style does the author use?

Ursula K. Le Guin’s writing style in “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” is marked by a blend of lyrical, descriptive prose and philosophical reflection. From the very beginning, Le Guin establishes a poetic and meditative tone, using rich, evocative descriptions to immerse the reader in the beauty of Omelas. Her use of vivid imagery is a key technique, particularly in the opening passages where she describes the Festival of Summer. The city of Omelas is brought to life through detailed sensory descriptions—bright colors, the sounds of bells, the smell of cooking food, and the graceful movements of people and animals. This imagery is not merely decorative; it draws the reader into the utopian world, making it feel tangible and real while also creating a stark contrast with the darker elements revealed later in the story.

One of Le Guin’s most notable techniques is her conversational narrative style, which directly addresses the reader and involves them in creating the story’s setting. The narrator frequently breaks the fourth wall, inviting the reader to imagine Omelas in their way. For instance, when discussing whether Omelas has advanced technology or practices certain customs, the narrator leaves these details open to interpretation, suggesting that the reader can shape the image of Omelas based on their own imagination. This interactive approach gives the narration a flexible, almost fluid quality, encouraging readers to engage with the story personally. This technique also heightens the story’s philosophical depth, as the narrator draws attention to the storytelling process and the difficulty of straightforwardly conveying complex ideas like happiness or morality.

Le Guin also makes skillful use of contrast as a narrative technique, particularly in her juxtaposition of the idyllic surface of Omelas and the grim reality that sustains it. The story begins with a glowing, almost dreamlike portrayal of a perfect society where the people are joyful and content, unburdened by the usual conflicts or inequalities of the world. This detailed depiction of beauty and celebration lulls the reader into accepting Omelas as an ideal place. However, this positive imagery is shattered when the narrator shifts to the hidden suffering of the child in the locked room. The stark contrast between the two settings—the radiant city above and the filthy, dark basement below—underscores the moral tension at the story’s heart. By presenting this sharp division between light and darkness, joy and misery, Le Guin forces readers to confront the uncomfortable truth that the happiness of many may depend on the suffering of a few.

Another technique that Le Guin employs effectively is ambiguity, both in the description of the city and in the moral questions the story raises. Omelas is described in broad, almost fantastical terms, but many details are left intentionally vague or open to interpretation. This ambiguity allows readers to fill in the gaps with their own ideas of what a utopia might look like, making Omelas both universal and personal. Similarly, the fate of the ones who walk away from Omelas is left unresolved. The narrator does not describe where they go or what they find, leaving their destination—and the implications of their choice—open to speculation. This deliberate lack of closure forces readers to engage deeply with the story’s themes, as the moral questions it raises are not answered by the author but left for the reader to grapple with.

Le Guin also uses repetition and rhetorical questions to emphasize key ideas and provoke reflection. Throughout the story, the narrator repeatedly asks the reader, “Do you believe?” or “How is one to tell about joy?” These questions highlight the challenge of describing pure happiness without falling into simplistic or clichéd expressions, prompting the reader to question their own assumptions about joy, suffering, and morality. The repetition of specific phrases, such as descriptions of the child’s suffering and the terms of the moral bargain in Omelas, reinforces the gravity of the situation and ensures that the reader does not easily forget the moral stakes of the story.

Finally, Le Guin’s use of philosophical reflection is a key aspect of her writing style in this story. The narrative is not just a description of events but a deep exploration of moral and ethical questions. The narrator frequently pauses to reflect on the nature of happiness, the justifications for suffering, and the limits of ethical reasoning. These reflections give the story a meditative, almost essayistic quality as if the narrator is guiding the reader through a process of moral inquiry. This technique allows Le Guin to engage with complex ideas without losing the story’s emotional impact, as the philosophical reflections are always grounded in the vivid, sensory details of the setting and the shocking revelation of the child’s suffering.

Conclusions and General Commentary on The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas by Ursula K. Le Guin

“The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” is a deeply thought-provoking story that challenges readers to examine the moral underpinnings of happiness, community, and individual responsibility. Through its haunting depiction of a seemingly perfect society that conceals a grim and troubling secret, Ursula K. Le Guin presents a moral parable that resonates far beyond the confines of its fictional setting. The ethical dilemma at the heart of the story—whether the joy of many can justify the suffering of one—echoes real-world situations where the comfort of some is built on the exploitation or oppression of others. This allegory forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about complicity, sacrifice, and the human tendency to rationalize injustice when it serves the greater good.

Le Guin’s use of ambiguity in the story enhances its timelessness and universality. Omelas, while presented as an idyllic city, is intentionally vague in many details, allowing readers to imagine it as they see fit. This flexibility makes the story more powerful, as Omelas can represent any society where people are forced to confront the uncomfortable trade-offs between collective well-being and individual suffering. The ones who walk away embody the moral courage to reject such compromises, even though their departure offers no clear resolution or solution to the problem. Their journey into the unknown suggests that moral integrity often requires stepping into uncertainty, a refusal to accept the status quo even when no better alternative is guaranteed. This open-ended conclusion challenges readers to think about their own values and the difficult choices they might face when confronted with similar ethical dilemmas.

One of the most compelling aspects of the story is its refusal to provide easy answers. Le Guin does not offer a simple moral judgment about the citizens who stay or those who leave; rather, she presents both choices as complex and fraught with difficulty. Those who remain in Omelas are not portrayed as villains but as individuals who have learned to live with the paradox of their happiness. Similarly, those who walk away are not described as heroes but as people who can no longer live with that paradox, even if it means embracing isolation and uncertainty. This moral ambiguity is central to the story’s power, as it encourages readers to wrestle with their own interpretations and conclusions rather than accepting a predefined moral stance.

Ultimately, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” mediates the nature of societal structures and the hidden costs of utopia. It forces us to ask what we are willing to sacrifice for comfort and happiness and whether such sacrifices can be truly justified. Le Guin’s story compels us to examine not only the structures of our own societies but also our personal role within those systems—whether we, like the citizens of Omelas, are complicit in the suffering of others or whether we have the courage to reject it and walk away. In this way, the story continues to provoke reflection on the tension between idealism and reality, making it a poignant and enduring piece of literature that speaks to both individual conscience and collective responsibility.